What is a model in psychology, you ask? It’s the secret sauce, the invisible scaffolding that helps us make sense of the wild, wonderful, and often baffling world of the human mind. Think of it as a map for the unseeable, a blueprint for the intangible, and a translator for the whispers of our inner lives. Without these conceptual tools, psychology would be a chaotic jumble of observations, a vast ocean of data with no compass to guide us.

This exploration dives deep into what these models are, how they’re built, and why they’re absolutely crucial for understanding ourselves and others.

At its core, a psychological model is an abstract representation designed to simplify and explain complex mental processes, behaviors, and their underlying mechanisms. These aren’t tangible objects you can hold, but rather conceptual frameworks that highlight key elements and their interactions. The fundamental purpose is to provide a structured way to organize, understand, and predict psychological phenomena. Core characteristics include their abstract nature, their focus on relationships between concepts, and their ability to be tested and refined.

The importance of abstract representation cannot be overstated; it allows us to move beyond mere description to deeper explanation and prediction, offering a lens through which to view the intricate workings of the psyche.

Defining Psychological Models

Yo, so what’s the deal with these “psychological models”? Think of ’em like blueprints for the brain, but way more chill. They ain’t the actual brain, nah, but they help us break down complicated stuff about how we think, feel, and act. It’s all about making sense of the messy human experience by building simplified versions of reality.These models are like the ultimate cheat codes for understanding ourselves and others.

They give us a framework, a way to organize all the random thoughts and feelings swirling around. Without ’em, psychology would be a total free-for-all, and nobody wants that. They’re essential for researchers to test theories and for therapists to help people out.

Fundamental Purpose of Psychological Models

The main gig of a psychological model is to simplify the complex. It’s like taking a massive, intricate machine – your mind – and drawing a diagram of its key parts and how they connect. This diagram isn’t the machine itself, but it helps you understand how it works, what makes it tick, and where things might be going sideways.

It’s all about creating a digestible representation so we can actually study and explain psychological phenomena.

Core Characteristics of Psychological Models

So, what makes something a legit psychological model? It’s gotta have a few key ingredients. First off, it’s an abstraction – meaning it’s not the real thing, but a simplified version. Then, it needs to be , giving us a reasonwhy* things happen. It should also be predictive, meaning it can give us a heads-up on what might happen next.

And finally, it’s gotta be testable, so we can see if it holds up in the real world.Here are some of the key traits:

- Abstraction: They strip away the unnecessary details to focus on the essential elements of a psychological process or structure.

- Simplification: They make complex phenomena easier to grasp by reducing them to manageable components and relationships.

- Representation: They offer a symbolic or conceptual depiction of mental processes, behaviors, or structures.

- Explanation: They aim to provide coherent accounts of how psychological phenomena occur and interact.

- Prediction: They often allow for educated guesses about future behavior or mental states under certain conditions.

- Testability: They should be formulated in a way that allows for empirical investigation and validation through research.

Importance of Abstract Representation in Psychological Modeling

Abstract representation is the secret sauce, the MVP of psychological modeling. It’s how we take something as intangible as a thought or an emotion and give it a form we can actually work with. Think about it: you can’t exactly put “anxiety” under a microscope. But a model can represent anxiety as a combination of physiological arousal, cognitive distortions, and behavioral avoidance.

This abstract representation allows us to isolate, analyze, and manipulate these components in our studies and treatments.For instance, consider the “Information Processing Model” of memory. It doesn’t show you the actual neurons firing, but it represents memory as a series of stages: encoding, storage, and retrieval. This abstract model allows psychologists to design experiments to test how efficiently information is encoded, how long it’s stored, and how easily it can be retrieved, leading to breakthroughs in understanding learning and forgetting.

“The purpose of a model is not to be right, but to be useful.”

George Box

This quote perfectly sums up the essence of psychological models. They are tools, designed to help us navigate and understand the human psyche, even if they don’t capture every single nuance of reality. They provide a lens through which we can observe, interpret, and ultimately, gain knowledge about ourselves.

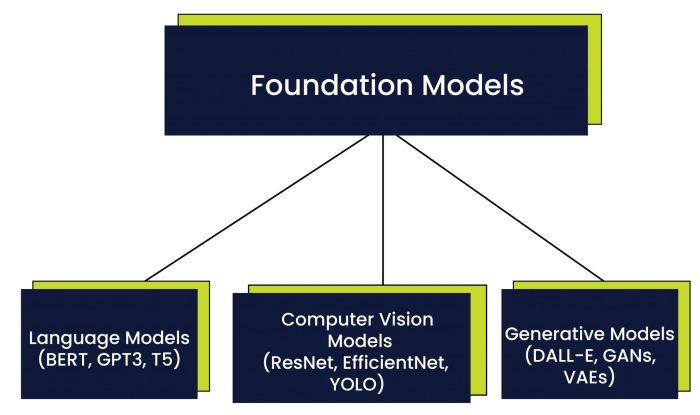

Types of Psychological Models

Yo, so we’ve already laid down what a psych model is, right? It’s like the blueprint for how our brains and behaviors work. But peep this, not all models are built the same. They got different vibes, different jobs. Understanding these types is key to really gettin’ the science behind the mind.

We’re talkin’ about how these models help us see, explain, and even guess what folks are gonna do.Think of it like different tools in a toolbox. You wouldn’t use a hammer to screw in a bolt, right? Same deal with psych models. Each type is designed for a specific mission, helping us break down complex mental stuff into something we can actually study and understand.

Let’s dive into the different flavors of these models and what makes them tick.

Theoretical Models vs. Empirical Models, What is a model in psychology

Alright, so when we talk about models, there are two main camps: theoretical and empirical. Theoretical models are the big ideas, the brainchildren of smart folks trying to make sense of things. They’re built on logic, existing knowledge, and sometimes pure intuition. They propose how stuff

- should* work. Empirical models, on the other hand, are grounded in data, the real deal. They’re built from observations and experiments, showing how stuff

- actually* works.

Theoretical models are like the initial concept art for a video game. They give you the vision, the characters, the world, but it’s not playable yet. They set the stage and guide the development. Empirical models are like the actual gameplay. They’re tested, refined, and based on what happens when you interact with the game.

They take those theoretical blueprints and see if they hold up in the real world of data. It’s a constant back-and-forth, with theory guiding research and research refining theory.

Descriptive Models in Psychological Research

Descriptive models are all about painting a picture. They’re like a photographer capturing a scene – they show you what’s there, how things are organized, and what the key features are. They don’t necessarily explainwhy* things are the way they are, but they give us a solid understanding of the landscape. These models are super useful for mapping out phenomena, identifying patterns, and giving us a baseline to work from.Here are some ways descriptive models are used to break down what we see:

- Surveys and Questionnaires: Imagine trying to figure out what the most popular music genres are among high schoolers. You’d use a survey to ask a bunch of people. The results, showing the percentages for each genre, are a descriptive model of music taste.

- Observational Studies: Think about how a biologist might describe the social structure of a chimpanzee troop, noting who leads, who follows, and how they interact. That detailed account is a descriptive model of their social dynamics.

- Case Studies: When psychologists study a single individual with a rare condition, like a unique learning disability, the detailed report of their symptoms, behaviors, and history is a descriptive model of that specific case.

Models in Understanding Psychological Phenomena

Now, models take it a step further. They’re not just showing you the picture; they’re telling you the story behind it. These models aim to uncover the causes, the mechanisms, and the relationships that make psychological phenomena happen. They’re like the detective trying to figure out motive and opportunity.

In psychology, a model serves as a simplified representation of complex mental processes, much like a blueprint guides construction. Understanding these conceptual frameworks often requires dedicated study, as one might ponder how long is a psychology masters degree , before returning to the essence of how these models illuminate the human psyche.

models seek to answer the “why” and “how” behind behavior and mental processes.

These models are crucial because understanding the underlying reasons allows us to predict future events, develop interventions, and even change behavior. For example, the “drive-reduction theory” in motivation explains why we eat or drink (to reduce the internal drive of hunger or thirst) rather than just describing that we eat when we’re hungry.

Predictive Models and Their Applications in Forecasting Behavior

Predictive models are the crystal balls of psychology, but way more scientific. They use patterns and relationships identified in data to forecast what’s likely to happen next. Think of them as sophisticated algorithms that can make educated guesses about future behavior based on past trends and current conditions. These are super important in areas where we need to anticipate outcomes.We see predictive models in action all over the place:

- Educational Psychology: Models can predict which students are at risk of dropping out based on their grades, attendance, and engagement levels. This allows schools to intervene early.

- Clinical Psychology: Therapists might use models to predict the likelihood of relapse for individuals with substance abuse disorders, helping them tailor treatment plans.

- Marketing and Consumer Behavior: Companies use predictive models to forecast which products customers are likely to buy based on their browsing history and past purchases, leading to personalized recommendations.

These models are constantly being refined with new data to improve their accuracy, making them powerful tools for decision-making.

Computational Models vs. Conceptual Models

Finally, let’s compare computational and conceptual models. Conceptual models are the big-picture ideas, the frameworks that organize our thinking. They’re like the general Artikel of an essay. Computational models, on the other hand, are much more detailed and often involve math and computer simulations. They’re like the actual written essay, with specific sentences, paragraphs, and arguments.

| Conceptual Models | Computational Models |

|---|---|

| Focus on abstract ideas and relationships. | Use mathematical equations and algorithms. |

| Often described in words or diagrams. | Can be simulated and tested using computers. |

| Provide a broad understanding of a phenomenon. | Can generate precise predictions and test specific hypotheses. |

| Example: Freud’s psychosexual stages of development. | Example: A neural network model simulating how the brain learns a new skill. |

While conceptual models give us the framework, computational models allow us to really dig in, test out theories with numbers, and see if they hold water in a simulated environment. They’re both vital for building a complete picture of the human mind.

Functions and Applications of Psychological Models

Yo, so we’ve been droppin’ knowledge on what psychological models are and the different flavors out there. Now, let’s get into why these things are straight-up essential, like the secret sauce in understanding how our minds and behaviors work. They ain’t just fancy theories; they’re tools that help us make sense of the world and even fix what’s broken.These models are like the blueprints for psychologists.

They help us take all the scattered pieces of information about human behavior and fit ’em together into something that makes sense. Think of it like building a dope playlist – you gotta organize those tracks to make the whole vibe flow. Models do the same for psychological knowledge, making it easier to digest and use.

Organizing and Synthesizing Psychological Knowledge

Psychology is a vast universe, packed with tons of research and observations about people. Without models, it’d be a chaotic mess, like trying to find a specific needle in a haystack the size of a planet. Models step in and act as our mental GPS, helping us map out this complex terrain. They give us a framework to connect different ideas, like how a good narrative connects plot points.Here’s how they do the heavy lifting:

- Structure and Order: Models provide a structured way to view psychological phenomena. They break down complex processes into manageable parts, showing how they relate to each other.

- Connecting the Dots: They highlight the relationships between different variables and concepts. This helps us see the bigger picture and understand the underlying mechanisms at play.

- Building Blocks: Think of models as building blocks. Each block represents a piece of knowledge, and the model shows how to stack them up to create a coherent understanding of a psychological concept.

- Reducing Complexity: By simplifying complex ideas, models make them easier to grasp and communicate. It’s like translating a complicated tech manual into something your grandma can understand.

Facilitating Hypothesis Generation

So, you’ve got your knowledge all organized, right? That’s cool and all, but what’s next? Models are also dope for sparking new ideas. They ain’t just about explaining what we already know; they’re about pushing the boundaries and figuring out what wedon’t* know yet. It’s like having a crystal ball that hints at future possibilities.The process goes a little somethin’ like this:

- Identifying Gaps: When you look at a model, you can often spot where things are missing or where the connections aren’t super clear. These gaps are prime real estate for new questions.

- Making Educated Guesses: Based on the existing structure of the model, you can make educated guesses, or hypotheses, about how things

-might* work. It’s like predicting the next plot twist in your favorite show based on the clues. - Predictive Power: A good model can predict certain outcomes. If the model says X leads to Y, then researchers can hypothesize that if we change X, Y should change too.

- Challenging Assumptions: Models can also make us question what we thought we knew. By presenting a new way of looking at things, they can lead to hypotheses that challenge old beliefs.

For example, the Attachment Theory model suggests that early caregiver relationships influence adult romantic relationships. This model leads to hypotheses like: “Individuals with secure attachment styles in childhood will exhibit greater relationship satisfaction in adulthood.” This is a testable prediction born directly from the model’s framework.

Guiding Research Design and Methodology

Once you’ve got a hypothesis, you gotta test it, right? Models are like the ultimate cheat sheet for figuring out how to do that. They tell you what to look for and how to measure it, so you don’t waste time running around in circles. It’s like having a detailed map before you embark on a treasure hunt.Models influence research in several key ways:

- Defining Variables: Models clearly Artikel the key variables that are important to study. This helps researchers know exactly what they need to measure.

- Specifying Relationships: They show how different variables are supposed to interact. This guides researchers in choosing statistical methods that can test these specific relationships.

- Choosing Methods: Depending on the model, researchers might opt for experiments, surveys, case studies, or observational research. The model points them in the right direction.

- Interpreting Findings: When the data comes back, the model provides a framework for understanding what it all means. It helps researchers decide if their results support or contradict the existing theoretical structure.

Consider the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) model, which posits that thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are interconnected. When researching CBT’s effectiveness for anxiety, researchers would design studies to measure changes in negative thought patterns (cognitions), anxiety levels (feelings), and avoidance behaviors. The model dictates the focus of their investigation.

Utility in Clinical Practice for Diagnosis and Intervention

Alright, let’s talk about the real-world impact. Models aren’t just for textbooks and labs; they’re crucial for helping people who are struggling. In the clinical world, they’re like the doctor’s diagnostic tools and treatment plans rolled into one. They help therapists understand what’s going on with a client and how to help them get better.Here’s the breakdown of their clinical power:

- Diagnosis: Models provide categories and criteria for understanding psychological disorders. They help clinicians differentiate between various conditions, ensuring accurate diagnosis.

- Treatment Planning: Based on the diagnosed issue and the theoretical model guiding the clinician, specific interventions are chosen. The model suggests the most effective pathways to recovery.

- Client Understanding: Models can help therapists explain a client’s experiences in a way that makes sense to them. This can reduce confusion and empower the client in their own healing process.

- Predicting Outcomes: While not perfect, models can offer insights into potential treatment outcomes and help manage client expectations.

Scenario: Applying the Transtheoretical Model in Therapy

Let’s paint a picture. Imagine a client, let’s call him Mark, who’s been struggling with heavy drinking for years. He comes to therapy, but he’s not really convinced he needs to stop. He just says his wife is making him come.A therapist using the Transtheoretical Model (Stages of Change), which breaks down the process of behavior change into distinct stages, would approach Mark differently than someone who doesn’t use a model.Here’s how it might go down:

The therapist starts by exploring Mark’s current feelings about his drinking. Instead of immediately pushing him to quit (which would likely backfire since he’s not ready), the therapist recognizes Mark is likely in the Precontemplation stage. He’s not thinking about changing his behavior and might even be defensive about it.

The therapist’s goal isn’t to force change but to help Mark move towards the next stage, Contemplation. They might ask open-ended questions like:

“What are some of the things you’ve noticed about your drinking lately?”

“What are your wife’s main concerns about it?”

The therapist might also gently introduce information about the potential negative impacts of heavy drinking, without judgment. The idea is to raise Mark’s awareness and encourage him to start thinking about the possibility of change, even if it’s just a flicker. The model guides the therapist to tailor their approach, meeting Mark where he is, rather than imposing a rigid solution.

If Mark starts to consider the pros and cons of his drinking, he’s moving into Contemplation, and the therapist can then use different strategies to help him prepare for change.

Components of Psychological Models

Yo, so we’ve been droppin’ knowledge on what these psych models are all about, right? Now, let’s get into the nitty-gritty, the building blocks, the actual stuff that makes these models tick. Think of it like dissecting a dope beat – you gotta know the drums, the bassline, the samples, and how they all come together to make that fire track.These models ain’t just random ideas thrown at the wall.

They’re structured, man. They got parts, and understanding these parts is key to understanding how psychologists explain why we do what we do. It’s like havin’ the blueprint for a mental mansion.

Variables, Relationships, and Assumptions

Alright, first up, we got variables. These are the things that can change or vary, the factors we’re lookin’ at. In psych models, these can be anything from how much sleep you get (obvious, right?) to how you’re feelin’ about your squad (way more complex). Then there are relationships, which are basically how these variables mess with each other. Does more sleep mean you’re less stressed?

That’s a relationship we’re tryna figure out. And don’t forget assumptions – these are the things the model creators just figure are true, the groundwork they build on, even if they ain’t directly tested. It’s like assuming gravity exists when you’re building a rocket; it’s a given.

Constructs and Operationalization

Now, let’s talk about constructs. These are the big, abstract ideas that psych models try to get a handle on, like intelligence, personality, or motivation. You can’t exactly grab ‘intelligence’ with your hands, right? So, we gotta operationalize it. That means we turn these fuzzy concepts into somethin’ we can actually measure, somethin’ concrete.

For example, to measure intelligence, we might use an IQ test score. That test score is the operational definition of intelligence in that specific model.

Latent Variables in Psychological Models

Sometimes, the stuff we wanna measure ain’t directly observable. These are called latent variables. Think about happiness. You can’t see happiness, but you can see someone smiling, or hear them laugh, or measure their self-reported mood. In a psych model, a latent variable like ‘happiness’ would be represented by a bunch of observable indicators.Here’s how it might look:

| Latent Variable | Observable Indicators |

|---|---|

| Happiness | Self-reported mood score |

| Frequency of smiling | |

| Number of positive social interactions |

Role of Parameters and Estimation

Parameters are the numerical values within a model that describe the relationships between variables. They’re like the knobs and dials on a soundboard, controlling how loud the bass is or how much reverb is on the vocals. Estimating these parameters means figuring out what those numbers should be based on real-world data. It’s how we make the model fit what’s actually happenin’ out there.

Common Types of Relationships

Psych models ain’t all about simple cause-and-effect. The connections between variables can get pretty wild. We gotta understand the different ways these things can interact.Here’s a rundown of some common relationship vibes you’ll see in these models:

- Linear Relationships: This is the most straightforward. As one variable goes up, the other goes up (or down) at a steady rate. Think of it like a straight line on a graph.

- Curvilinear Relationships: Here, the relationship ain’t a straight shot. It might go up and then down, or vice versa. Like how stress can improve performance up to a point, then it tanks it.

- Interactive Relationships: This is where the effect of one variable on another

-depends* on the level of a third variable. It’s like how a good beat sounds even better with a dope rapper, but a weak rapper can mess it up, even with a killer beat.

Evaluating and Refining Psychological Models: What Is A Model In Psychology

Yo, so we’ve been talkin’ ’bout these psychological models, right? They’re like the blueprints for how our minds work. But just ’cause you got a blueprint doesn’t mean it’s gonna build a dope crib. We gotta check if these models are legit, if they actually work in the real world, and if they can handle different vibes. It’s all about makin’ sure they’re solid and stay relevant.Think of it like this: you build a dope new video game.

It looks sick, the graphics are fire, but does it actually play well? Does it crash every five minutes? Is it fun for everyone, or just your crew? Evaluating and refining models is the same hustle. We gotta test ’em, see where they mess up, and then level ’em up.

Assessing Model Validity and Reliability

When we’re checkin’ out a psychological model, we gotta make sure it’s not just some made-up fairy tale. We’re lookin’ for two main things: validity and reliability. Validity means the model actually measures what it claims to measure. Is it gettin’ to the heart of the matter, or just playin’ peek-a-boo? Reliability means if you run the same test or observe the same phenomenon again, you get pretty much the same results.

It’s like a consistent DJ – always droppin’ the right beats.Here’s the lowdown on how we check for this:

- Construct Validity: This is about whether the model truly captures the theoretical concept it’s supposed to represent. For example, if a model claims to measure “anxiety,” does it actually hit all the key features of anxiety – the worry, the physical symptoms, the avoidance behaviors? We use different types of evidence to back this up, like convergent validity (does it correlate with other measures of anxiety?) and discriminant validity (does it

-not* correlate with things it shouldn’t, like intelligence?). - Criterion Validity: This checks if the model’s predictions line up with real-world outcomes. If a model predicts academic success, does it actually predict who will do well in school? This can be predictive (predicting future outcomes) or concurrent (predicting current outcomes).

- Internal Consistency: This is a big one for reliability. It means that all the different parts of the model (like questions in a survey or components of a theory) are measuring the same underlying thing. If a model has multiple indicators for “happiness,” do they all point to happiness, or are some pointing to something else entirely? Cronbach’s alpha is a common stat here.

- Test-Retest Reliability: This is straightforward. You give the same assessment or observe the same behavior at two different times, and if the scores are similar, it’s reliable. Think of it like a reliable weather forecast – if it says rain today and rain tomorrow, and it actually rains both days, that’s good test-retest reliability.

- Inter-Rater Reliability: This is crucial when human judgment is involved. It means that different observers or raters, using the same model or criteria, come to similar conclusions. If two therapists are using a model to diagnose depression, do they end up with the same diagnosis for the same patient?

Model Fitting and Goodness-of-Fit Indices

Alright, so we’ve got our data, and we’ve got our model. Now we gotta see how well the model actually “fits” the data. This is where model fitting comes in. It’s like trying to squeeze a puzzle piece into its spot – we’re lookin’ for that perfect snug fit. If the model doesn’t fit well, it’s probably not telling us the whole story.We use statistical techniques to see how closely the model’s predictions match the actual data we collected.

And to tell us if the fit is any good, we got these things called “goodness-of-fit indices.” They’re basically scores that tell us how well the model is representing the data.Here are some of the main players in the model fitting game:

- Chi-Square Test ($\chi^2$): This is a classic. It compares the observed data to what the model predicts. A non-significant chi-square means the model fits the data well. But, and this is a big “but,” it’s super sensitive to sample size. Big samples can make even a good model look bad.

- Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA): This is one of the most popular indices. It estimates the discrepancy between the model and the population covariance matrix, adjusted for model complexity. Lower values are better. We’re usually happy with RMSEA < 0.08, and really stoked with < 0.05.

- Comparative Fit Index (CFI): This index compares the proposed model to a “null” model (which assumes no relationships between variables). Higher values indicate a better fit. We’re lookin’ for CFI > 0.90, and ideally > 0.95.

- Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) / Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI): Similar to CFI, these indices also compare the proposed model to a baseline model. Higher values are better, and we’re aiming for > 0.90 or > 0.95.

- Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR): This measures the average difference between the observed and predicted correlations. Lower values are better, with < 0.08 usually considered a good fit.

It’s important to look at a combination of these indices, not just one, to get a full picture of how well the model is doing.

Testing Model Robustness

So, our model looks good in one experiment, with one group of people. But is it a one-hit wonder, or can it hold up under different conditions? That’s where testing robustness comes in. We gotta see if the model’s still spittin’ truth when we throw different variables its way, or when we test it on different crowds.This is how we make sure our models aren’t just a fluke.

We want ’em to be like a classic track that still bumps no matter who’s listenin’ or where they are.Methods for checking robustness include:

- Cross-Validation: This is a major key. You take your data, split it into two sets: a training set and a testing set. You build and fit the model on the training set, then see how well it performs on the unseen testing set. If it holds up, that’s a good sign.

- Subgroup Analysis: We run the model on different subgroups within our sample. For instance, if we’re studying a model of stress, we might test it separately for men and women, or for different age groups, or people from different socioeconomic backgrounds. Does the model explain stress similarly across these groups, or does it break down for some?

- Different Contexts: If the model was developed in a lab setting, we’d want to see if it applies in a real-world setting, like a school or a workplace. Or, if it was tested in one country, we might try to replicate the findings in another country with different cultural norms.

- Varying Measurement Methods: If the model uses self-report questionnaires, we might try to test it using behavioral observations or physiological measures. Does the core relationship or process described by the model still hold?

If the model performs consistently across these different tests, we can be way more confident in its generalizability.

Iterative Model Development and Refinement

Science ain’t static, and neither are psychological models. They’re not born perfect; they’re built, tested, tweaked, and rebuilt. This is the iterative nature of model development. It’s a cycle of build, test, learn, and improve.Think of it like a rapper workin’ on their album. They lay down a track, listen back, realize a verse is weak, rewrite it, re-record it, and then move on.

Each step makes the final product better.The process looks something like this:

- Conception: It all starts with an idea, a theory, or an observation that needs explaining.

- Initial Model Building: Based on existing knowledge, researchers construct a preliminary model.

- Data Collection: Researchers gather data that can be used to test the model.

- Model Fitting: The model is statistically fitted to the data, and goodness-of-fit indices are examined.

- Evaluation: The model’s validity, reliability, and robustness are assessed using the criteria we talked about.

- Identification of Weaknesses: If the model doesn’t fit well, or if it shows weaknesses in certain areas, researchers identify what needs to be improved. This could be a specific parameter, a relationship between variables, or even the overall structure.

- Model Refinement: The model is modified based on the identified weaknesses. This might involve adding new variables, removing unnecessary ones, or changing the hypothesized relationships.

- Re-testing: The refined model is then tested again with new data or the same data to see if the changes have improved its performance.

This cycle continues until the model is deemed sufficiently accurate, reliable, and useful for explaining the phenomenon it aims to represent. New evidence and discoveries can always lead to further refinements down the line.

Lifecycle of a Psychological Model

Here’s a visual representation of how a psychological model goes from a fresh idea to a polished tool, and then potentially back for a glow-up. It’s a continuous loop, always gettin’ better.

| Lifecycle of a Psychological Model | ||

| Phase 1: Conception & Initial Development | Step 1: Idea Generation Observation, theory, research gap. |

Phase 2: Testing & Evaluation |

| Step 2: Initial Model Construction Hypothesizing relationships, defining variables. |

||

| Step 3: Data Collection Gathering empirical evidence. |

||

| Phase 3: Refinement & Revision | Step 4: Model Fitting Assessing how well the model fits the data. |

Phase 4: Application & Further Research |

| Step 5: Validity & Reliability Assessment Checking if it measures what it should and is consistent. |

||

| Step 6: Robustness Testing Testing across different populations and contexts. |

||

| Step 7: Model Refinement Modifying the model based on evaluation results. |

||

| Step 8: Application in Research & Practice Using the model to explain, predict, and intervene. This can lead back to Phase 1 with new observations. |

||

Illustrative Examples of Psychological Models

![Black Models At Paris Haute Couture Fashion Week | [site:name] | Essence What is a model in psychology](https://i2.wp.com/modelagency.one/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/the-model-book-podcast.jpg?w=700)

Yo, so we’ve been talking about what these psychological models are all about, breaking ’em down and seeing how they work. Now, let’s get down to the nitty-gritty and check out some real-deal examples that show these models in action. It’s like seeing the blueprints turn into a dope building, you know? These examples are gonna help us understand how psychologists use these frameworks to make sense of the crazy, complex world of the human mind.

Information Processing Model of Memory

This model is all about how we take in, store, and then pull out information, kinda like a computer. It breaks down memory into a few key stages that happen one after another. Think of it as a pipeline for your thoughts.The Information Processing Model views memory as a series of stages, much like how a computer processes data. This perspective helps us understand the journey of information from initial input to eventual recall.

- Encoding: This is the first step, where your brain takes information from the outside world and transforms it into a format it can understand and store. It’s like typing something into a keyboard; the computer has to translate your keystrokes into digital signals. This can happen automatically, like remembering where you parked your car, or it can be effortful, like trying to memorize a new phone number.

- Storage: Once encoded, the information needs to be kept somewhere. This stage is about maintaining that information over time. Think of it as saving a file on your hard drive. Memory storage isn’t just one big vault; it’s believed to involve different systems, like short-term memory (for immediate tasks) and long-term memory (for stuff you remember for ages).

- Retrieval: This is the final act, where you pull that stored information back into conscious awareness. It’s like opening a file to read it. Sometimes retrieval is super easy, like remembering your best friend’s name. Other times, it’s a struggle, like trying to recall a specific detail from a movie you watched years ago.

Key processes within this model include attention (what you focus on), rehearsal (repeating information to keep it active), and organization (structuring information to make it easier to remember).

Social Cognitive Theory Model

This theory, championed by Albert Bandura, is all about how we learn by watching others and how our thoughts, behaviors, and environment all interact and influence each other. It’s not just about what happens

- to* us, but also what we

- think* about it and what we

- do* in response.

The Social Cognitive Theory emphasizes that learning is a complex interplay of internal mental processes and environmental influences, rather than a simple stimulus-response reaction.

- Reciprocal Determinism: This is the core idea here. It means that our behavior, our personal factors (like our beliefs and thoughts), and our environment all push and pull on each other. It’s a two-way street, or even a three-way street! For example, if you believe you’re good at math (personal factor), you’re more likely to tackle challenging math problems (behavior), which might lead to positive feedback from your teacher (environment), further boosting your confidence.

- Observational Learning: This is what most people think of when they hear “Social Cognitive Theory.” It’s learning by watching others, called models. We see what they do, what happens to them, and then we might imitate that behavior. Think about kids learning to tie their shoes by watching their parents, or how you might pick up a new dance move by watching a music video.

Bandura identified four key steps for observational learning: attention (you gotta notice it), retention (you gotta remember it), reproduction (you gotta be able to do it), and motivation (you gotta want to do it).

Biopsychosocial Model

This model is a big deal when it comes to understanding health, especially mental health. Instead of just looking at one thing, like biology or just your environment, it takes a holistic approach. It says that your well-being is a mashup of biological, psychological, and social factors.The Biopsychosocial Model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding health and illness by integrating multiple dimensions of human experience.

- Biological Factors: This covers the physical stuff – your genes, your brain chemistry, any illnesses you might have, your diet, how much you sleep. It’s all the physical machinery that makes you tick.

- Psychological Factors: This is about your mind – your thoughts, your emotions, your beliefs, your personality, how you cope with stress, your self-esteem. It’s your internal world.

- Social Factors: This includes your relationships with others, your family, your friends, your community, your job, your culture, your socioeconomic status. It’s the external network you’re a part of.

The application of this model to mental health is huge. It means that to treat something like depression, you can’t just look at brain chemicals. You also need to consider how someone’s thinking patterns are affecting them, and how their social support system (or lack thereof) is playing a role. It’s about treating the whole person, not just a single symptom.

Comparing Personality Models: Five-Factor vs. Psychodynamic

Let’s switch gears and talk about personality. Psychologists have come up with different ways to describe what makes each of us unique. Here, we’ll compare two major players: the Five-Factor Model and the Psychodynamic Model. They approach personality from totally different angles.This table breaks down the key differences and similarities between two influential models of personality, highlighting their distinct theoretical underpinnings and focus.

| Feature | Five-Factor Model (Big Five) | Psychodynamic Model |

|---|---|---|

| Core Idea | Personality is made up of five broad traits that are relatively stable and measurable. | Personality is shaped by unconscious drives, childhood experiences, and internal conflicts. |

| Focus | Observable behaviors and self-reported traits. | Unconscious mind, defense mechanisms, and early life development. |

| Key Components | Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism (OCEAN). | Id, Ego, Superego; defense mechanisms (e.g., repression, denial); psychosexual stages. |

| Methodology | Empirical research, questionnaires, statistical analysis. | Clinical observation, case studies, dream analysis, free association. |

| Nature vs. Nurture | Acknowledges both, with a significant emphasis on biological/genetic predispositions. | Strong emphasis on early childhood experiences and environmental influences shaping the unconscious. |

| Goal of Therapy | Understanding and managing traits; improving functioning. | Bringing unconscious conflicts into conscious awareness to resolve them. |

Predicting Academic Performance with a Simple Regression Model

Now, let’s get a little mathematical, but keep it simple. Regression models are super useful in psychology for predicting outcomes. Imagine we want to figure out how well a student might do in school. We can use a simple regression model to see if their study habits have anything to do with their grades.This example demonstrates how a statistical tool can be used to quantify the relationship between variables and make predictions, offering a practical application of psychological concepts.Let’s say we collect data on a group of students.

We measure two things:

- Study Hours: The number of hours per week each student spends studying.

- GPA: Their Grade Point Average at the end of the semester.

A simple linear regression model would try to find a line that best fits the data points, showing the relationship between study hours and GPA. The basic idea is to predict GPA based on study hours.The formula for a simple linear regression is often represented as:

Y = a + bX

Where:

- Y is the dependent variable (what we want to predict) – in this case, GPA.

- X is the independent variable (what we think influences Y) – in this case, Study Hours.

- a is the y-intercept (the predicted GPA when Study Hours are zero).

- b is the slope of the line (how much GPA is predicted to change for every one-hour increase in Study Hours).

For example, if our regression analysis shows:

GPA = 1.5 + 0.2

(Study Hours)

This means that, on average, for every extra hour a student studies per week, their GPA is predicted to increase by 0.2 points. So, if a student studies 10 hours a week, their predicted GPA would be 1.5 + 0.2

- 10 = 3.5. If they study 20 hours a week, their predicted GPA would be 1.5 + 0.2

- 20 = 5.5 (though GPAs usually cap at 4.0, so this highlights that models have limits and real-world data might need adjustments). This shows how we can use models to make educated guesses about future performance based on observable behaviors.

Last Point

So, we’ve journeyed through the fascinating landscape of psychological models, from their fundamental purpose to their intricate components and the rigorous process of their evaluation. We’ve seen how these abstract yet powerful tools are not just academic curiosities but vital instruments for scientific inquiry, clinical practice, and our collective quest to understand the human experience. Whether it’s charting the pathways of memory, deciphering the dynamics of social interaction, or unraveling the complexities of personality, psychological models provide the essential frameworks that illuminate the path forward, constantly being refined by new evidence and deeper insights.

They are the architects of our understanding, shaping how we perceive, interpret, and ultimately, interact with the world around and within us.

Question & Answer Hub

What’s the difference between a theory and a model in psychology?

While often used interchangeably, a theory is a broader, more general explanation for a phenomenon, while a model is a more specific, often visual or structural representation of a theory’s key components and their relationships. Models operationalize theories.

Can psychological models be wrong?

Absolutely. Psychological models are simplifications of reality. They are constantly tested against new data, and if the evidence doesn’t support them, they are revised, refined, or even discarded in favor of better explanations.

Are all psychological models quantitative?

No. While many models are quantitative, involving statistical relationships and parameters, conceptual models are qualitative and focus on describing relationships and processes without necessarily assigning numerical values.

How do models help in everyday life?

Even without realizing it, we use simplified mental models to navigate social situations, make decisions, and understand others’ behavior. Formal psychological models just make these processes explicit and testable.

What happens if a model is too complex?

If a model becomes overly complex, it risks losing its power and becoming difficult to test or apply. The goal is often to find the simplest model that adequately explains the data (parsimony).