What is a hypothesis in psychology, that’s the core question we’re diving into. It’s the bedrock of scientific inquiry, the educated guess that fuels discovery. Without it, research would be a ship adrift, lacking direction or purpose. This exploration will illuminate its fundamental nature, its critical role in the scientific method, and how to craft one that truly propels our understanding of the human mind.

We’ll dissect the essential characteristics that elevate a mere idea into a testable hypothesis, distinguishing between the null and alternative statements that form the backbone of empirical investigation. From there, we’ll chart a course through the iterative journey of forming, testing, and refining these crucial conjectures, ensuring they are not only clear and specific but also falsifiable and measurable, the hallmarks of robust psychological research.

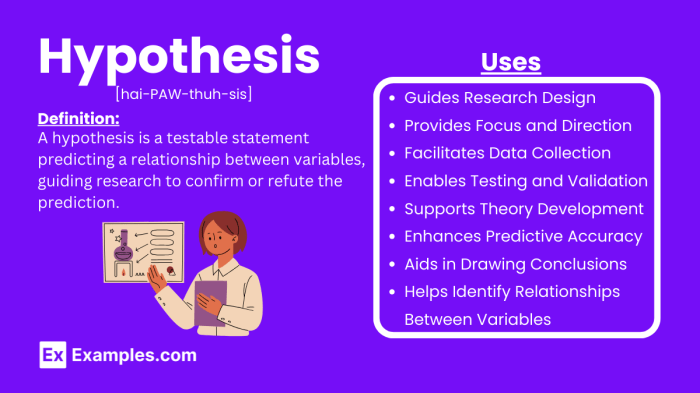

Defining a Psychological Hypothesis

In the vast expanse of psychological inquiry, a hypothesis stands as a luminous beacon, a tentative yet potent proposition that guides our exploration into the intricate landscapes of the human mind and behavior. It is the nascent seed from which rigorous research blossoms, a carefully crafted statement that anticipates a relationship or effect, awaiting the crucible of empirical evidence to affirm or refute its existence.

Without this guiding star, the journey of discovery would be a meandering drift, devoid of direction and purpose.The fundamental nature of a hypothesis in psychological research is that of a testable prediction. It is not a mere guess or an opinion, but rather a specific, falsifiable statement that can be subjected to systematic investigation. It bridges the abstract realm of theory with the concrete world of observable phenomena, allowing researchers to move from broad conceptualizations to specific, measurable outcomes.

This predictive power is what imbues a hypothesis with its scientific value, transforming speculation into a structured quest for knowledge.

Essential Characteristics of a Testable Hypothesis

For a statement to ascend to the status of a testable hypothesis in psychology, it must possess certain defining qualities. These characteristics ensure that the proposed idea can be rigorously examined, yielding clear and interpretable results. A hypothesis must be clear and unambiguous, leaving no room for misinterpretation. Its terms should be precisely defined, allowing for operationalization – the translation of abstract concepts into measurable variables.

Furthermore, a hypothesis must be empirical, meaning it can be tested through observation and experimentation, rather than relying on philosophical reasoning or personal belief. Crucially, it must be falsifiable; there must be a conceivable outcome of the research that would prove the hypothesis incorrect. This principle of falsifiability is a cornerstone of scientific methodology, ensuring that our understanding is built upon evidence that has withstood scrutiny.A hypothesis should also be specific, outlining a clear relationship between variables.

Vague statements lack the precision needed for effective testing. For instance, a hypothesis stating that “stress affects memory” is less useful than one specifying the direction and nature of that effect. The variables involved must be clearly identifiable and measurable. This often involves defining how abstract psychological constructs, such as “stress” or “memory,” will be operationally defined and quantified in the study.

Types of Hypotheses in Psychological Studies

In the architecture of psychological research, hypotheses often appear in pairs, representing opposing yet complementary predictions. These are the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis, each playing a distinct role in the process of statistical inference. The null hypothesis, often denoted as H₀, represents the default assumption of no effect or no relationship between variables. It is the statement that the researcher aims to disprove.

The alternative hypothesis, denoted as H₁ or Hₐ, is the statement that contradicts the null hypothesis, proposing that there is indeed an effect or a relationship. It is the outcome the researcher hopes to find evidence for.The interplay between these two hypotheses forms the bedrock of statistical hypothesis testing. Researchers gather data and use statistical methods to determine whether the evidence is strong enough to reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis.

This process is akin to a courtroom trial, where the null hypothesis is the accused presumed innocent until proven guilty, and the alternative hypothesis represents the prosecution’s claim.

Examples of Null and Alternative Hypotheses

To illuminate these concepts, consider a study investigating the impact of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance.

A researcher might formulate the following hypotheses:

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): There is no statistically significant difference in cognitive performance scores between individuals who are sleep-deprived and those who are not.

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): Individuals who are sleep-deprived will exhibit significantly lower cognitive performance scores compared to those who are not.

Another example could be a study examining the effectiveness of a new therapy for anxiety.

Here, the hypotheses might be:

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): The new therapy has no significant effect on reducing anxiety levels.

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): The new therapy significantly reduces anxiety levels.

In these examples, the null hypothesis posits a state of no change or no difference, while the alternative hypothesis proposes a specific effect or relationship. The statistical analysis of collected data will then guide the researcher in deciding whether to reject the null hypothesis, thereby lending support to the alternative hypothesis.

“A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested and falsified.”

The Role of Hypotheses in the Scientific Method

A hypothesis, in the realm of psychological inquiry, is not merely a whisper of an idea, but a guiding star, a luminous thread woven through the intricate tapestry of scientific exploration. It is the seed from which the mighty oak of knowledge grows, providing direction and purpose to the arduous journey of understanding the human mind and its myriad behaviors.

Without this foundational concept, the pursuit of psychological truth would be a wandering in a labyrinth, devoid of a compass or a map.This guiding principle shapes the very contours of our investigations, dictating the questions we ask, the methods we employ, and the observations we deem significant. It acts as a beacon, illuminating the path ahead, ensuring that our efforts are focused and our discoveries meaningful.

The hypothesis transforms raw curiosity into a structured quest, a systematic endeavor to unravel the complexities that lie within.

Guiding the Process of Psychological Investigation

The hypothesis serves as the architect of our research design, dictating the blueprint for uncovering psychological truths. It is the initial spark that ignites the investigative fire, providing a clear statement of what we anticipate discovering. This pre-defined expectation then sculpts the research questions, shaping them into testable propositions rather than vague curiosities. Consequently, the hypothesis dictates the specific variables that will be measured, the participants who will be studied, and the experimental or observational procedures that will be implemented.For instance, a researcher hypothesizing that “increased exposure to nature reduces self-reported stress levels” will design studies that systematically vary exposure to natural environments and measure stress using validated questionnaires.

This hypothesis guides the selection of appropriate statistical analyses, ensuring that the data collected can effectively address the proposed relationship. It transforms the broad landscape of human experience into a focused, manageable area of study, allowing for rigorous and systematic examination.

The Relationship Between a Hypothesis and Observable Data

The hypothesis stands as a bridge, a vital conduit connecting the abstract realm of theory to the concrete world of observable phenomena. It is a predictive statement, an educated guess about how certain psychological constructs will manifest in measurable ways. The strength of a hypothesis lies in its falsifiability; it must be formulated in such a way that empirical evidence can either support or refute it.

This empirical grounding is the bedrock of psychological science, ensuring that our understanding is built upon observation rather than speculation.Consider the hypothesis: “Individuals who engage in regular mindfulness meditation will exhibit lower levels of anxiety compared to those who do not.” To test this, observable data would be gathered through standardized anxiety scales administered to both groups. Heart rate variability, a physiological indicator of stress, could also be measured.

The hypothesis, therefore, provides a framework for interpreting these collected data points, allowing researchers to ascertain whether the observed differences align with the initial prediction.

“A hypothesis is a tentative explanation for a phenomenon that can be tested through scientific investigation.”

The Iterative Process of Hypothesis Formation, Testing, and Refinement

The journey of psychological discovery is rarely a linear march; it is, rather, a dynamic, cyclical dance of hypothesis, evidence, and renewed inquiry. The initial hypothesis, once tested, rarely emerges unscathed. The data gathered, like a discerning critic, may affirm the hypothesis, demanding further exploration to solidify its validity. More often, however, the findings reveal nuances, limitations, or even outright contradictions, prompting a period of reflection and refinement.This iterative process begins with the formation of a hypothesis, often born from existing theories or preliminary observations.

This hypothesis is then rigorously tested through empirical research. The results of this testing phase are then analyzed, and based on these findings, the original hypothesis may be:

- Supported: If the data align with the prediction, the hypothesis gains credibility and may lead to further research exploring its boundaries or implications.

- Refuted: If the data contradict the prediction, the hypothesis is discarded or significantly modified. This refutation is as valuable as support, as it redirects research efforts towards more accurate explanations.

- Modified: Often, the results suggest that the hypothesis needs adjustment. This might involve refining the variables, considering mediating or moderating factors, or broadening or narrowing the scope of the original prediction.

This continuous loop of hypothesis formation, empirical testing, and subsequent refinement is the engine that drives psychological knowledge forward, ensuring that our understanding of the human psyche evolves and becomes increasingly sophisticated. For example, early hypotheses about learning might have been simple associations, but iterative testing revealed the complex roles of reinforcement schedules, cognitive processes, and social influences, leading to more nuanced and accurate theories.

Formulating Effective Psychological Hypotheses

To sculpt a hypothesis, one must first perceive the whispers of curiosity, the faint echoes of questions that dance at the edge of understanding. It is a delicate art, this translation of an unformed thought into a tangible, testable proposition. The journey from a nebulous inquiry to a precise prediction requires a keen eye for detail and a disciplined approach to the unfolding landscape of the mind.The crafting of a robust psychological hypothesis is akin to a cartographer charting unknown territories.

It demands clarity, specificity, and a deep commitment to the principles of scientific inquiry. Without these guiding stars, our explorations risk becoming lost in the wilderness of ambiguity.

Steps in Crafting a Clear and Specific Psychological Hypothesis

Embarking on the creation of a psychological hypothesis is a journey through several essential stages, each building upon the last to forge a statement that is both illuminating and rigorously testable. These steps are the bedrock upon which empirical investigation is built, ensuring that our inquiries are directed with purpose and precision.

- Identify the Core Inquiry: The genesis of any hypothesis lies in a question that sparks the researcher’s imagination. This initial question, however broad, must be distilled into a focused area of investigation. For instance, instead of “Does social media affect mood?”, a more refined inquiry might be “How does the frequency of passive social media consumption influence self-reported levels of loneliness in young adults?”

- Define Key Constructs: Once the inquiry is narrowed, the crucial elements within it—the variables—must be precisely defined. These are the abstract concepts that will be measured or manipulated. For “passive social media consumption,” this might be operationalized as “the number of hours spent scrolling through social media feeds without active engagement (liking, commenting, posting) per week.” For “loneliness,” it could be measured using a validated scale like the UCLA Loneliness Scale.

- Propose a Relationship: The heart of a hypothesis is the proposed connection between these defined constructs. This connection can be directional (e.g., increased consumption leads to increased loneliness) or non-directional (e.g., social media consumption is related to loneliness). A directional hypothesis offers a stronger prediction.

- Formulate a Testable Statement: The final step is to weave these elements into a clear, declarative sentence that states the expected relationship. This statement must be unambiguous and open to empirical verification.

Translating Research Questions into Actionable Hypotheses

The transition from a broad research question to a sharp, actionable hypothesis is a critical bridge in the scientific process. It requires transforming the exploratory nature of a question into a predictive statement that can be directly investigated through data collection and analysis. This transformation imbues the research with direction and purpose.Consider the research question: “What is the impact of mindfulness meditation on stress levels in university students?” To translate this into actionable hypotheses, we must first identify the key variables: mindfulness meditation and stress levels.

- Identify Variables: In this case, the independent variable is mindfulness meditation (what is being manipulated or introduced), and the dependent variable is stress levels (what is being measured for change).

- Operationalize Variables: We must then define how these variables will be measured. Mindfulness meditation could be operationalized as participation in a daily 20-minute guided meditation program for eight weeks. Stress levels could be operationalized by measuring cortisol levels in saliva or by using a standardized stress questionnaire administered weekly.

- Formulate a Predictive Statement: Based on existing literature or theoretical frameworks, a prediction is made about the relationship between the operationalized variables.

A potential set of actionable hypotheses could be:

- Directional Hypothesis: University students who participate in a daily 20-minute guided mindfulness meditation program for eight weeks will exhibit significantly lower self-reported stress levels compared to a control group receiving no meditation training.

- Null Hypothesis: There will be no significant difference in self-reported stress levels between university students who participate in a daily 20-minute guided mindfulness meditation program for eight weeks and a control group receiving no meditation training.

These hypotheses are actionable because they specify the intervention, the population, the duration, and the expected outcome, allowing for a direct empirical test.

Ensuring a Hypothesis is Falsifiable and Measurable

The very essence of a scientific hypothesis lies in its ability to be tested and, crucially, to be proven wrong. This principle of falsifiability, championed by philosopher Karl Popper, is the hallmark of empirical science. A hypothesis that cannot be disproven, no matter the evidence, resides in the realm of belief rather than scientific inquiry. Measurability, on the other hand, ensures that the concepts within the hypothesis can be empirically observed and quantified, providing the data necessary for testing.To ensure a hypothesis is falsifiable, it must make a specific prediction about the observable world.

If the predicted outcome does not occur, the hypothesis can be rejected or modified. For example, the hypothesis “Children who are exposed to violent video games will exhibit increased aggressive behavior” is falsifiable because aggressive behavior can be observed and measured. If studies consistently show no increase in aggression, the hypothesis would be challenged.Measurability is achieved by defining the variables in a way that allows for concrete observation and quantification.

This is where operational definitions become paramount.Let us consider the hypothesis: “Increased exposure to nature positively impacts mood.”To ensure this hypothesis is measurable and falsifiable, we must operationalize the terms:

- Exposure to Nature: This could be measured by the number of hours spent in natural environments (parks, forests) per week, or by the frequency of visits to green spaces.

- Mood: This can be measured using validated psychological scales such as the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) or the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

A falsifiable and measurable version of the hypothesis would be:

“University students who spend at least five hours per week in natural environments will report significantly higher scores on the Positive Affect subscale of the PANAS compared to students who spend less than one hour per week in natural environments.”

This statement is falsifiable because empirical data can be collected on the number of hours spent in nature and the scores on the PANAS. If the data shows no significant difference, or even a negative correlation, the hypothesis would be falsified. The specificity of the time commitment and the measurement tool provides the necessary groundwork for empirical scrutiny.

Types of Psychological Hypotheses

Within the labyrinth of psychological inquiry, hypotheses unfurl like delicate blossoms, each possessing a unique hue and form, guiding the seeker through the intricate landscape of the human mind. These conceptual seeds, planted with careful thought, blossom into varied structures, each designed to illuminate a specific facet of our being. Understanding their distinctions is akin to recognizing the different constellations in the night sky, each offering a unique pattern of understanding.The journey through psychological research is often charted by the compass of its hypotheses.

These guiding stars, though sharing the common aim of illuminating truth, take on distinct shapes and intentions. Some point with unwavering certainty towards a predicted outcome, while others cast a wider net, seeking any glimmer of connection. Some delve into the dance of association, observing how variables move together, while others strive to unravel the intricate threads of cause and effect, seeking the hand that pulls the strings.

Directional Versus Non-Directional Hypotheses

The scientist’s gaze, when formulating a hypothesis, can be either sharply focused or broadly cast. A directional hypothesis is like a seasoned archer, aiming their arrow with precision at a specific target, predicting the exact nature of the relationship between variables. Conversely, a non-directional hypothesis is like a curious explorer, venturing into uncharted territory, acknowledging a connection may exist but leaving the direction of its flow open to discovery.A directional hypothesis is a confident whisper of what is expected.

For instance, a researcher might hypothesize that:

- Increased exposure to nature will lead to a significant decrease in reported levels of stress among urban dwellers.

- Students who engage in mindfulness meditation for 15 minutes daily will demonstrate higher scores on standardized tests compared to those who do not.

These statements leave no room for ambiguity; they predict a specific direction of influence.A non-directional hypothesis, on the other hand, acknowledges a potential link without predetermining its form. It’s a more cautious, yet equally valid, exploration. An example might be:

- There will be a significant relationship between social media usage and self-esteem in adolescents.

- The type of music listened to during study sessions will affect cognitive performance.

Here, the researcher is open to finding a positive, negative, or even a complex interaction, simply seeking evidence of a connection.

Correlational Versus Causal Hypotheses

In the vast tapestry of psychological phenomena, relationships between variables can be observed in two fundamental ways: as intertwined threads or as a chain of command. Correlational hypotheses explore the former, seeking to understand how two or more variables move in tandem, like dancers mirroring each other’s steps. Causal hypotheses, however, aim to identify the choreographer, seeking to establish that one variable directly influences or causes a change in another, much like a conductor leading an orchestra.Correlational hypotheses are the observers of association.

They propose that a relationship exists, but do not claim that one variable is the cause of the other. Consider these examples:

- A positive correlation will be found between the number of hours spent exercising and reported levels of happiness.

- There is a negative correlation between the frequency of social interactions and symptoms of loneliness.

These hypotheses suggest that as one variable changes, the other tends to change in a predictable way, but they do not assert that exercise

- causes* happiness or that social interaction

- causes* a reduction in loneliness. Other factors might be at play.

Causal hypotheses are the architects of explanation, seeking to establish a direct link of influence. They propose that a change in one variable will lead to a change in another. For instance:

- Watching violent television programs in childhood will cause an increase in aggressive behavior in adolescence.

- Providing positive reinforcement for completing homework will cause a decrease in procrastination among students.

Establishing causality is a more rigorous endeavor, often requiring experimental designs where researchers can manipulate the presumed cause and observe its effect while controlling for extraneous variables.

Hypotheses Across Psychological Domains

The hypotheses that bloom within psychology are as diverse as the human experiences they seek to understand, each rooted in a particular soil of inquiry. Whether exploring the intricate dance of social interactions, the silent workings of the mind, or the profound depths of developmental change, these guiding statements take on specific forms, reflecting the unique questions posed by each domain.

Social Psychology

In the realm where individuals interact and influence one another, hypotheses often focus on group dynamics, attitudes, and interpersonal behavior.

- Conformity: Individuals are more likely to conform to group norms when the group is perceived as unanimous and the task is ambiguous.

- Attribution: People tend to attribute the successes of others to external factors (luck, opportunity) and their own successes to internal factors (skill, effort).

- Prejudice: Exposure to positive intergroup contact under conditions of equal status and common goals will reduce intergroup prejudice.

Cognitive Psychology

This domain delves into the inner workings of the mind, exploring processes such as memory, attention, perception, and problem-solving.

- Memory Encoding: Deeper levels of semantic processing lead to better long-term recall of information compared to shallow levels of phonological processing.

- Attention: The Stroop effect demonstrates that naming the color of ink of a word is slower and more error-prone when the word itself is a different color name (e.g., the word “blue” written in red ink).

- Problem Solving: Providing individuals with a functional fixedness-breaking intervention will increase their ability to solve insight problems.

Developmental Psychology

Here, hypotheses examine the changes that occur throughout the lifespan, from infancy to old age, in areas such as cognition, emotion, and social relationships.

- Attachment Theory: Infants who develop secure attachments with their primary caregivers will exhibit greater exploration and resilience in novel situations.

- Language Acquisition: Children exposed to a rich and varied linguistic environment will develop more complex language skills at an earlier age.

- Cognitive Decline: Engaging in mentally stimulating activities throughout adulthood is associated with a slower rate of cognitive decline in later life.

Clinical Psychology

This branch focuses on understanding, preventing, and treating mental disorders, and hypotheses often guide the development and evaluation of interventions.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Patients undergoing CBT for depression will show a greater reduction in depressive symptoms compared to those receiving a placebo treatment.

- Anxiety Disorders: Exposure therapy is effective in reducing avoidance behaviors associated with specific phobias.

- Trauma: Early intervention with trauma-focused therapy following a traumatic event will mitigate the long-term development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Common Pitfalls in Hypothesis Formulation

As the sculptor shapes the marble, so too must the psychologist refine the hypothesis, lest the raw stone remain unformed, a mere whisper of potential. The journey from a nascent idea to a testable proposition is fraught with shadows, where vagueness can obscure clarity and untestability can render even the most brilliant insight inert. To navigate this delicate terrain requires a keen eye for the subtle errors that can derail the most promising research.The path of discovery is often paved with the discarded fragments of hypotheses that failed to take flight.

These are not merely academic missteps but profound impediments, capable of grounding a research endeavor before it even has a chance to soar. Recognizing these common pitfalls is the first step towards forging hypotheses that are not only elegant in their conception but robust in their capacity to illuminate the human psyche.

The Siren Song of Vagueness

When a hypothesis drifts in the nebulous sea of ambiguity, it loses its anchor to empirical reality. A hypothesis must be a clear beacon, not a mist that dissolves upon approach. If its terms are ill-defined, its relationships unclear, its predictions shrouded in metaphor, then the tools of science will find no purchase, and the quest for knowledge will be left adrift.Consider a hypothesis such as: “People will feel better after interacting with nature.” While intuitively appealing, this statement is a tapestry woven with vague threads.

What constitutes “feeling better”? Is it a reduction in anxiety, an increase in happiness, a sense of calm? What is “interacting with nature”? A brief walk in a park, a week-long wilderness expedition, or simply gazing at a potted plant? Without precise operational definitions, this hypothesis is akin to trying to catch moonlight in a sieve – an endeavor destined for futility.

The Specter of Untestability

A hypothesis, however profound its philosophical implications, remains a phantom if it cannot be subjected to empirical scrutiny. If its core tenets lie beyond the reach of observation, measurement, or experimentation, it cannot serve as a guiding star for scientific inquiry. Such hypotheses, though perhaps poetic in their grandiosity, are ultimately sterile, offering no fertile ground for the growth of verifiable knowledge.A classic example of an untestable hypothesis might be: “The unconscious mind dictates all our actions.” While this concept is central to certain psychodynamic theories, formulating a hypothesis that directly and definitively tests the entirety of this assertion in a falsifiable manner presents immense challenges.

How does one empirically isolate and measure the complete dictation of the unconscious on every action? If a hypothesis proposes a supernatural influence or a phenomenon that cannot be observed or manipulated, it becomes a matter of faith rather than scientific investigation.

The Tangled Web of Correlation and Causation

A frequent misstep in hypothesis formulation is the conflation of correlation with causation, a subtle yet critical distinction that can lead research astray. Observing that two variables move in tandem does not, in itself, prove that one causes the other. This is a common trap, where the allure of a simple explanation overshadows the complexity of underlying mechanisms.Imagine a hypothesis stating: “Increased ice cream sales are directly responsible for a rise in crime rates.” While statistical data might reveal a correlation between these two phenomena, particularly during warmer months, it is a leap of logic to infer causation.

The omitted variable, the warmer weather, likely influences both ice cream consumption and the propensity for certain outdoor activities that may correlate with increased crime. A poorly formulated hypothesis here would fail to account for such confounding factors, leading to erroneous conclusions.

The Shadow of Confirmation Bias

Formulating a hypothesis with a predetermined outcome in mind, seeking only evidence that supports a cherished belief, is a path that leads away from objective truth. Confirmation bias, the tendency to favor information that confirms pre-existing beliefs, can insidiously warp the hypothesis-building process, turning it into a self-fulfilling prophecy rather than a genuine exploration.A researcher deeply convinced that a particular therapeutic technique is universally effective might formulate a hypothesis designed toprove* its success, rather than to

test* its efficacy under various conditions. For instance, a hypothesis might be phrased as

“The XYZ therapy will lead to significant improvements in all patients.” This phrasing pre-supposes success and may lead to the selective interpretation of data, overlooking instances where the therapy was less effective or even detrimental. A more robust hypothesis would acknowledge the possibility of varying outcomes and seek to understand the conditions under which the therapy is most beneficial.

The Peril of Overly Complex or Multifaceted Hypotheses

When a hypothesis attempts to explain too much, to encompass too many variables and relationships, it becomes unwieldy and difficult to test. Like a knot tied with too many strands, it can unravel under the slightest strain, obscuring the very phenomenon it seeks to illuminate.Consider a hypothesis that posits: “Childhood exposure to violent video games, coupled with parental neglect and a genetic predisposition to aggression, will inevitably lead to adult criminal behavior.” While each of these factors may indeed play a role, attempting to test this intricate web of interactions within a single hypothesis is a monumental task.

It becomes challenging to isolate the unique contribution of each variable and to control for their complex interplay. This can lead to a research design that is overly ambitious, underpowered, and ultimately inconclusive.

Visualizing Hypothesis Testing (Conceptual)

To grasp the essence of hypothesis testing, imagine a sculptor chiseling away at a block of marble, revealing the form hidden within. In psychology, our marble is raw data, and the chisel is the rigorous process of testing, seeking to uncover the truth about human behavior. This journey is not one of mere speculation, but a structured exploration, guided by our initial hypothesis.The visualization of this process allows us to see the abstract become tangible.

It’s a dance between anticipation and evidence, where the elegance of a well-formed hypothesis meets the stark reality of empirical observation. Through visual metaphors, we can illuminate the path from a tentative idea to a substantiated claim, or the humbling moment when an idea is gently set aside.

The Sculptor’s Studio: A Metaphor for Hypothesis Testing

Picture a grand studio, bathed in soft, diffused light. At its center stands a massive block of uncarved marble, representing the vast, unknown landscape of psychological phenomena. Before this block, a sculptor stands, holding a preliminary sketch – this sketch is our psychological hypothesis, a blueprint of the form they believe lies within.The tools in the sculptor’s hands are our research methods: the sharp chisels of experiments, the fine brushes of surveys, the sturdy hammers of statistical analysis.

Each stroke, each chip of marble removed, is a piece of data collected. The goal is to see if the emerging form aligns with the initial sketch. If the marble, as it is shaped, begins to resemble the sketch, the hypothesis is supported, and the sculptor rejoices in their insight. However, if the form takes an unexpected turn, deviating from the sketch, it doesn’t mean failure, but rather a revelation of a different, perhaps more intricate, beauty.

The hypothesis, in this case, is refuted, prompting a re-evaluation and a new sketch for the next endeavor.

Elements of the Visual Metaphor, What is a hypothesis in psychology

The visual narrative of hypothesis testing unfolds through several key symbolic elements, each contributing to the understanding of the scientific endeavor.

- The Marble Block: This represents the raw, uninterpreted reality of human behavior and mental processes. It is vast, complex, and holds many potential truths.

- The Sculptor: The researcher, driven by curiosity and a desire to understand, is the active agent in this process.

- The Preliminary Sketch: This is the hypothesis itself – a specific, testable prediction about the relationship between variables. It is the initial vision of the form to be revealed.

- The Sculpting Tools: These embody the various research methodologies employed. Different tools are suited for different tasks, just as different research designs are appropriate for different questions. This includes the precise instruments of controlled experiments, the broader strokes of observational studies, and the meticulous detailing of statistical analyses.

- The Emerging Form: As the sculptor works, the form within the marble begins to take shape. This represents the data being collected and analyzed.

- Alignment with the Sketch: If the emerging form closely matches the preliminary sketch, it provides evidence to support the hypothesis. The sculptor’s vision is validated.

- Deviation from the Sketch: If the emerging form diverges significantly from the sketch, it suggests the hypothesis may not accurately reflect the reality. This does not invalidate the process, but rather offers an opportunity for new discoveries and revised hypotheses.

A Hypothetical Experiment: The Luminescence of Learning

Consider a hypothesis: “Students who engage in active recall of study material will demonstrate superior retention compared to those who passively re-read the material.” This is our preliminary sketch.The marble block is the collective memory of a group of students. The sculptor is the researcher. The tools are a carefully designed experiment. One group of students (Group A) is instructed to actively recall information from a textbook chapter by writing down key points from memory.

The other group (Group B) is instructed to simply re-read the same chapter multiple times.After a week, both groups are given a comprehensive test on the material. The scores on this test represent the emerging form. If Group A’s scores are significantly higher than Group B’s, our emerging form aligns with the sketch. The hypothesis is supported. The sculptor has revealed the predicted pattern in the marble.

If, however, there is no significant difference, or if Group B performs better, the sketch was perhaps inaccurate, and the sculptor must re-examine their tools and their initial vision. This refutation is not an end, but a new beginning, prompting a revised hypothesis, perhaps exploring

- how* active recall is implemented or

- what type* of material is being studied.

Hypotheses in Different Research Designs

The tapestry of psychological inquiry is woven with diverse threads, each demanding a unique hue for its guiding hypotheses. As we venture into the realm of research, the very form and function of our hypotheses shift, adapting to the landscape of the design chosen to illuminate the human mind. From the controlled crucible of experimentation to the watchful gaze of observation, and from the structured metrics of quantification to the rich narrative of qualitative exploration, hypotheses must gracefully dance to the rhythm of the methodology.The architect of research, when drawing up plans for understanding behavior, must consider the fundamental nature of the questions being posed and the tools available to seek answers.

Hypotheses, those delicate seedlings of prediction, are sown in soil prepared by the chosen design, their growth nurtured by the specific conditions of inquiry.

Hypotheses in Experimental Versus Observational Studies

In the grand theater of psychological research, experimental and observational designs represent two distinct lenses through which we view the intricate workings of the mind and behavior. The hypotheses formulated for each are as varied as the methodologies themselves, reflecting the degree of control and the nature of the inferences we aim to draw.Experimental studies, with their deliberate manipulation of variables, allow for hypotheses that posit causal relationships.

The researcher actively intervenes, creating conditions to test whether a specific factor, the independent variable, indeed leads to a change in another, the dependent variable. This allows for a more direct and assertive statement of prediction.

In experimental research, hypotheses often take the form of a directional prediction: “Increasing exposure to positive social media content will lead to a significant increase in self-esteem.”

Observational studies, conversely, observe phenomena as they naturally occur, without manipulation. Here, hypotheses are more often concerned with describing relationships, associations, or patterns between variables. The emphasis shifts from “cause and effect” to “what is related to what.”

For observational studies, a hypothesis might be phrased as: “There is a significant positive correlation between the amount of time spent in nature and reported levels of happiness.”

The distinction lies in the researcher’s role: an active agent of change in experiments, versus a passive, yet keen, observer in observational studies. This difference dictates the precision and assertiveness with which a hypothesis can be stated.

A hypothesis in psychology is a testable prediction, often the cornerstone of research. Understanding the time commitment, such as how many years for a masters in psychology , is crucial before formulating such testable statements. Ultimately, a solid hypothesis drives the entire scientific inquiry process.

Hypotheses in Qualitative Versus Quantitative Research

The pursuit of psychological understanding can be undertaken through a spectrum of approaches, broadly categorized as quantitative and qualitative. These differing epistemologies shape not only the data collected but also the very essence of the hypotheses that guide the inquiry.Quantitative research, with its emphasis on numbers, measurement, and statistical analysis, typically employs hypotheses that are precise, testable, and often directional.

These hypotheses seek to quantify relationships and generalize findings to larger populations. They are the bedrock of deductive reasoning, moving from a general theory to specific predictions.

A quantitative hypothesis might be: “Students who engage in daily mindfulness exercises for 15 minutes will score, on average, 10 points higher on a standardized anxiety scale compared to a control group.”

Qualitative research, on the other hand, delves into the richness of human experience, seeking depth, meaning, and context. Hypotheses in this realm are often less pre-determined and more emergent, allowing for exploration and discovery. They may be broader, more open-ended, and subject to refinement as the research unfolds.

In qualitative research, a hypothesis might emerge as an initial guiding question or proposition, such as: “Exploring the lived experiences of individuals who have overcome significant trauma will reveal common themes of resilience and post-traumatic growth.”

The formulation of hypotheses in qualitative research is often an iterative process, beginning with a general area of interest and evolving into more specific propositions as patterns and insights are uncovered through data analysis. This inductive approach allows the research to be guided by the participants’ own narratives and perspectives.

Hypotheses in Exploratory Versus Confirmatory Research

Within the broader landscape of psychological inquiry, research can be broadly classified as either exploratory or confirmatory, and the role of hypotheses shifts accordingly. These distinctions are crucial for understanding the direction and purpose of the investigation.Exploratory research is undertaken when little is known about a phenomenon, or when seeking to generate new theories and ideas. In this context, hypotheses are not rigid predictions to be tested but rather tentative propositions or guiding questions that direct the initial exploration of the data.

They serve as a compass, pointing towards areas of potential interest rather than dictating specific outcomes.

Hypotheses in exploratory research are often framed as statements of potential association or areas of inquiry, such as: “There may be a relationship between early childhood temperament and adolescent risk-taking behaviors.” This guides the researcher to look for such connections without pre-supposing their nature or strength.

Confirmatory research, in contrast, begins with established theories or prior findings and aims to test specific predictions derived from them. Here, hypotheses are clearly stated, testable propositions that the researcher seeks to confirm or refute through rigorous data analysis. This approach is rooted in deductive reasoning.

A confirmatory hypothesis is a direct, testable statement: “Based on social cognitive theory, individuals who witness aggressive behavior will be more likely to exhibit aggressive behavior themselves when placed in a similar situation.”

The distinction between these two types of research highlights the dynamic nature of hypothesis development. Exploratory research allows for the “discovery” of hypotheses, while confirmatory research focuses on the “testing” of pre-defined ones. The choice between these approaches dictates the rigor with which hypotheses are formulated and the nature of the conclusions that can be drawn.

Final Summary

So, what is a hypothesis in psychology? It’s the spark that ignites the scientific flame, the guiding star that leads researchers through the labyrinth of human behavior and cognition. We’ve navigated its definition, its indispensable role in the scientific method, and the art of its formulation, alongside the common pitfalls to sidestep. Understanding and mastering the hypothesis is not just an academic exercise; it’s the key to unlocking deeper insights and driving meaningful progress in our quest to comprehend the complexities of the mind.

Frequently Asked Questions: What Is A Hypothesis In Psychology

What’s the difference between a research question and a hypothesis?

A research question is broad and seeks to explore a topic, while a hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction derived from that question, stating an expected relationship between variables.

Can a hypothesis be proven true?

In science, hypotheses are not definitively “proven” true. Instead, research provides evidence that either supports or fails to support the hypothesis. The goal is to build confidence in a hypothesis through repeated testing.

What happens if a hypothesis is not supported by the data?

If a hypothesis is not supported, it’s not a failure. It means the initial prediction was incorrect, which still yields valuable information. Researchers then refine their hypotheses or explore alternative explanations, contributing to the iterative nature of scientific discovery.

Is it possible to have multiple hypotheses for one research question?

Yes, it’s common to have multiple hypotheses for a single research question, especially if the question is complex. Each hypothesis might explore a different aspect or relationship related to the overarching question.

What is a directional hypothesis?

A directional hypothesis predicts the specific direction of the expected relationship between variables (e.g., “increased study time will lead to higher exam scores”). A non-directional hypothesis predicts a relationship exists but doesn’t specify the direction.