what is a correlation in psychology sets the stage for this enthralling narrative, offering readers a glimpse into a story that is rich in detail with a mysterious tone and brimming with originality from the outset. Imagine a hidden map where psychological phenomena are mere landmarks, and correlation is the invisible ink revealing the secret pathways between them. This exploration delves into the very essence of how different aspects of the human mind and behavior intertwine, hinting at patterns that lie just beyond our immediate grasp.

At its heart, correlation in psychological research is the statistical technique used to determine the extent to which two or more variables fluctuate together. It’s about uncovering whether a change in one thing is associated with a change in another, painting a picture of their relationship without necessarily dictating the cause. Think of it as observing that when the moon waxes, the tides tend to rise; the two events are linked, but one doesn’t directly command the other.

This fundamental concept allows psychologists to identify potential connections, paving the way for deeper investigations into the intricate workings of the mind.

Defining Correlation in Psychological Research

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/correlation_defintion_-9d2d662781724d61af6d6322a2a294b5.jpg?w=700)

Correlation is a fundamental concept in psychology that helps us understand the relationships between different variables. It’s not about cause and effect, but rather about how two things tend to move together. In essence, when one variable changes, does another variable also tend to change in a predictable way? This understanding is crucial for building theories and making predictions about human behavior and mental processes.The primary purpose of establishing correlations in psychological research is to identify patterns and associations.

By observing how variables relate, researchers can gain insights into the underlying mechanisms of psychological phenomena. This can lead to the development of new hypotheses, the refinement of existing theories, and the design of interventions aimed at influencing behavior or improving mental well-being.

The Fundamental Concept of Correlation, What is a correlation in psychology

Correlation describes the statistical relationship between two or more variables. It quantifies the extent to which these variables vary together. When we talk about correlation, we are interested in whether an increase or decrease in one variable is associated with an increase or decrease in another. It is important to remember that correlation does not imply causation; just because two things are related doesn’t mean one causes the other.

Definition of Correlation in Psychological Studies

In the context of psychological studies, a correlation is a statistical measure that describes the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two variables. This measure, known as the correlation coefficient, typically ranges from -1.0 to +1.0. A positive correlation indicates that as one variable increases, the other also tends to increase. A negative correlation suggests that as one variable increases, the other tends to decrease.

A correlation close to 0 indicates a weak or no linear relationship between the variables.

Purpose of Establishing Correlations

The primary purpose of establishing correlations in psychological research is to explore and understand the associations between various psychological constructs. This helps researchers to:

- Identify potential relationships that warrant further investigation.

- Develop and test hypotheses about how different psychological factors interact.

- Make predictions about future behavior or outcomes based on observed relationships.

- Inform the development of interventions and therapies by highlighting key contributing factors.

A Simple Analogy for Correlation

Imagine you are observing children playing in a park. You might notice that on days when the sun is shining brightly, more children tend to be playing outside. This is a simple illustration of a positive correlation: as the “sunshine” variable increases, the “number of children playing outside” variable also tends to increase. Conversely, on days with heavy rain, fewer children might be playing outside.

This would represent a negative correlation: as “rain” increases, “number of children playing outside” decreases. This analogy highlights how two things can be observed to happen together, without one necessarily causing the other (e.g., the sun doesn’t directly cause children to play, but the pleasant weather it brings does).

Types of Correlations and Their Interpretation

Understanding the different types of correlations helps us make sense of the relationships between psychological variables. Just like recognizing different signs in our journey of learning, identifying these correlation types allows us to predict and understand how one thing might relate to another in the human mind and behavior.The correlation coefficient, a number between -1 and +1, is the key to understanding these relationships.

It tells us not only if a relationship exists but also its direction and strength. This numerical value is like a compass, guiding us through the complex landscape of psychological research.

Positive Correlation

A positive correlation indicates that as one variable increases, the other variable also tends to increase. Conversely, as one variable decreases, the other also tends to decrease. This means the two variables move in the same direction.A hypothetical psychological example of a positive correlation could be the relationship between the number of hours a student studies and their exam scores.

Generally, as a student dedicates more hours to studying, their exam scores tend to be higher.

Negative Correlation

A negative correlation signifies that as one variable increases, the other variable tends to decrease, and vice versa. The variables move in opposite directions.An example of a negative correlation in psychology could be the relationship between the amount of time spent playing video games and academic performance. It is often observed that as the time spent on video games increases, academic performance might decrease.

Zero Correlation

A zero correlation suggests that there is no discernible linear relationship between the two variables. Changes in one variable do not systematically relate to changes in the other.For instance, a hypothetical example of zero correlation might be the relationship between a person’s shoe size and their anxiety levels. There is no logical reason to expect that larger shoe sizes would lead to higher or lower anxiety, or vice versa.

The Correlation Coefficient Range and Extremes

The correlation coefficient (often denoted by ‘r’) ranges from -1.0 to +1.0.

- r = +1.0: This represents a perfect positive linear correlation. As one variable increases, the other increases proportionally.

- r = -1.0: This indicates a perfect negative linear correlation. As one variable increases, the other decreases proportionally.

- r = 0: This signifies no linear correlation between the variables.

It is important to remember that perfect correlations (exactly +1 or -1) are very rare in psychological research due to the complexity of human behavior.

Interpreting the Strength of a Correlation

The absolute value of the correlation coefficient (ignoring the sign) indicates the strength of the relationship. The closer the value is to 1 (either +1 or -1), the stronger the correlation.

The strength of a correlation is judged by how far the coefficient is from zero.

A commonly used guideline for interpreting the strength is:

- 0.00 to 0.10: Negligible correlation.

- 0.10 to 0.39: Weak correlation.

- 0.40 to 0.69: Moderate correlation.

- 0.70 to 0.89: Strong correlation.

- 0.90 to 1.00: Very strong correlation.

For example, a correlation coefficient of r = 0.75 indicates a strong positive relationship, while r = -0.60 indicates a moderate negative relationship.

Variables Exhibiting Positive Correlations

Many psychological variables tend to move together, indicating a positive association. Understanding these patterns can help in making informed predictions.The following are common psychological variables that might exhibit positive correlations:

- Hours of sleep and mood

- Level of social support and self-esteem

- Frequency of exercise and physical health

- Academic achievement and motivation

- Amount of time spent practicing a skill and proficiency in that skill

- Proximity to a loved one and feelings of happiness

- Exposure to positive affirmations and self-efficacy

Variables Exhibiting Negative Correlations

Conversely, some psychological variables tend to move in opposite directions, suggesting a negative relationship. Recognizing these inverse relationships is equally valuable.The following are common psychological variables that might exhibit negative correlations:

- Stress levels and concentration ability

- Amount of procrastination and task completion rate

- Number of perceived threats and feelings of safety

- Social isolation and reported loneliness

- Aggressive behavior and prosocial behavior

- Screen time before bed and sleep quality

- Perfectionistic tendencies and overall life satisfaction

Measuring Correlation

In psychology, understanding the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables is crucial. To quantify this relationship, we use statistical measures that provide a numerical value, allowing for objective comparison and interpretation. These measures help us move beyond simply observing that two things seem connected to understanding precisely how connected they are.These statistical tools are the backbone of quantitative psychological research, enabling us to make sense of the complex interplay between human thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

They are the instruments that allow us to translate observations into meaningful data, forming the basis for scientific conclusions and further research.

Correlation vs. Causation: A Critical Distinction

In our journey to understand psychological research, it’s crucial to grasp a fundamental principle: correlation does not automatically mean causation. Just because two things tend to happen together does not mean one directly causes the other. This distinction is vital for interpreting research findings accurately and avoiding misleading conclusions that could impact our understanding of human behavior.Correlation describes a relationship where two variables change together.

For instance, we might observe that as ice cream sales increase, so do instances of sunburn. This is a positive correlation. However, it would be incorrect to assume that eating ice cream causes sunburn, or vice versa. The real culprit is likely a third factor: hot weather. When it’s hot, people buy more ice cream and also spend more time in the sun, leading to sunburn.

Understanding correlation in psychology reveals the interconnectedness of human experiences, much like how your journey toward healing might involve exploring can i be a therapist with a masters in psychology. This wisdom illuminates the paths available for growth. Recognizing these connections, even in career aspirations, deepens our grasp of what is a correlation in psychology.

This highlights how a shared underlying cause can create a correlation without a direct causal link between the observed variables.

Understanding Spurious Correlations

A spurious correlation occurs when two variables appear to be related but are not causally linked. Instead, their relationship is coincidental or due to a third, unmeasured variable. These can be particularly deceptive because they look statistically significant.A classic example of a spurious correlation is the observed relationship between the number of films Nicolas Cage appeared in each year and the number of people who drowned by falling into a swimming pool.

Data has shown a strong positive correlation between these two variables over several years. However, it is highly improbable that Nicolas Cage’s acting choices directly influence drowning incidents. The most likely explanation is that both variables are influenced by other, unrelated societal trends or random fluctuations. For instance, perhaps in years when Nicolas Cage was more prolific, the general economy was also doing well, leading to more disposable income for leisure activities (like swimming) and potentially more film production.

Common Pitfalls in Interpreting Correlational Data

Researchers must exercise caution when interpreting correlational data to prevent drawing incorrect conclusions. Several common errors can arise from misinterpreting the nature of the relationship between variables.

Researchers must actively avoid the following pitfalls:

- Assuming causation: The most frequent mistake is to infer that because two variables are correlated, one must be causing the other. This overlooks the possibility of third variables or reverse causation.

- Ignoring third variables: Failing to consider or measure potential confounding variables that might be influencing both correlated variables is a significant oversight.

- Directionality problem: When a correlation exists, it is often unclear which variable is the cause and which is the effect. For example, if we find a correlation between low self-esteem and depression, it’s hard to say whether low self-esteem leads to depression or if depression leads to low self-esteem.

- Overgeneralization: Applying findings from a specific correlational study to broader populations or different contexts without sufficient evidence can be misleading.

Thought Experiment: The Penguin and The Penguin Suit

To illustrate how two variables can be correlated without one causing the other, let us imagine a thought experiment. Consider the number of penguins observed in a specific zoo exhibit and the number of people wearing penguin suits at a local convention held on the same day.

Let’s analyze this scenario:

- Observation: On days when there are many penguins in the zoo exhibit, there is also a high attendance at the penguin suit convention. This would appear as a positive correlation.

- Misleading Inference: One might mistakenly conclude that the presence of more penguins at the zoo causes more people to wear penguin suits, or vice versa.

- The Real Reason: The actual reason for this correlation is likely a shared underlying event or interest. Perhaps the convention is related to a popular animated movie featuring penguins, and this event also drives increased interest in visiting the zoo’s penguin exhibit. Alternatively, a local “Penguin Appreciation Day” might be the cause, encouraging both zoo visits and costume participation. The zoo’s penguin population and the convention’s attendance are both effects of a common cause, not cause and effect of each other.

Scenario of Mistaken Causation Inference

Imagine a researcher studying the relationship between social media use and anxiety levels in adolescents. The researcher collects data and finds a strong positive correlation: adolescents who spend more time on social media tend to report higher levels of anxiety.

In this scenario, a researcher might mistakenly infer causation if they are not careful:

- The Mistake: The researcher might conclude that increased social media use directly causes anxiety in adolescents.

- Why it’s Misleading: This conclusion overlooks several possibilities. It could be that adolescents who are already experiencing anxiety are more likely to seek solace or distraction on social media. In this case, anxiety would be the cause, and social media use would be the effect.

- Other Factors: Furthermore, other factors could be contributing to both increased social media use and anxiety, such as peer pressure, academic stress, or underlying personality traits. Without further experimental research designed to isolate variables, the correlational data alone cannot definitively establish a causal link.

Applications of Correlation in Psychology: What Is A Correlation In Psychology

Correlation plays a vital role in psychology by helping researchers understand the intricate connections between different psychological variables. It allows us to explore patterns and associations that might not be immediately obvious, guiding our understanding of human behavior and mental processes. While correlation does not imply causation, it serves as a crucial stepping stone for generating hypotheses and making informed predictions.Correlational studies are fundamental across various psychological disciplines, providing a lens through which to examine complex relationships.

By identifying these associations, psychologists can develop a deeper understanding of phenomena, formulate testable hypotheses, and even predict future outcomes based on observed patterns.

Correlation in Social Psychology

Social psychology extensively uses correlation to investigate how individuals interact and are influenced by their social environment. Researchers explore relationships between attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, and social factors. For instance, studies might examine the correlation between the amount of time spent on social media and levels of self-esteem, or the association between perceived social support and overall life satisfaction. These correlations help social psychologists understand the dynamics of group behavior, persuasion, and interpersonal relationships.

Correlation in Developmental Psychology

In developmental psychology, correlation is instrumental in tracking how psychological characteristics change over the lifespan and how different developmental milestones relate to one another. Researchers might investigate the correlation between early language exposure and later cognitive abilities, or the relationship between parental warmth and a child’s emotional regulation skills. Such findings help in understanding typical developmental trajectories and identifying potential areas of concern or intervention.

Correlation in Clinical Psychology

Clinical psychology relies heavily on correlation to identify potential links between symptoms, risk factors, and treatment outcomes. For example, studies may explore the correlation between childhood trauma and the development of adult anxiety disorders, or the relationship between adherence to medication and recovery rates in individuals with schizophrenia. These correlational findings are essential for understanding the etiology of mental health conditions and for developing effective diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Identifying Potential Relationships Between Psychological Constructs

Correlation provides a powerful tool for uncovering potential relationships between abstract psychological constructs that cannot be directly observed. By measuring these constructs through various psychological assessments and surveys, researchers can determine if they tend to co-vary. For example, a psychologist might hypothesize that there is a relationship between a person’s level of conscientiousness (a personality trait) and their academic performance.

By measuring conscientiousness and academic grades in a group of students, they can calculate a correlation coefficient to see if higher conscientiousness is associated with higher grades.

Correlation quantifies the degree to which two variables move in relation to each other.

Hypothesis Generation for Future Experimental Research

The identification of significant correlations often sparks the development of new hypotheses that can then be tested through experimental research. When a strong positive or negative correlation is observed, it suggests a potential underlying causal link that warrants further investigation under controlled conditions. For instance, if a correlational study finds a strong positive relationship between regular exercise and improved mood, this might lead researchers to design an experiment where one group is assigned to an exercise regimen and another to a control condition to see if exercise directly causes an improvement in mood.

Prediction in Psychological Contexts

Correlational data is invaluable for making predictions in various psychological settings. While not establishing causation, the strength and direction of a correlation allow for probabilistic statements about one variable based on the known value of another. For example, in educational psychology, a strong positive correlation between scores on a standardized aptitude test and subsequent college GPA can be used to predict a student’s likelihood of academic success.

Similarly, in organizational psychology, a correlation between certain personality traits and job performance can help predict which candidates might be most successful in a particular role.

Applications of Correlation Across Psychological Research Areas

Correlation is a versatile tool applied across numerous subfields of psychology. The table below illustrates how it aids in understanding and predicting phenomena in different areas.

| Psychological Research Area | Application of Correlation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Social Psychology | Understanding social influences on behavior and attitudes. | Examining the correlation between peer group influence and adolescent risk-taking behaviors. |

| Developmental Psychology | Tracking developmental changes and interrelationships between milestones. | Investigating the correlation between early social interaction and the development of empathy in young children. |

| Clinical Psychology | Identifying risk factors and symptom associations for mental health conditions. | Assessing the correlation between sleep disturbances and symptoms of depression. |

| Educational Psychology | Predicting academic performance and identifying factors influencing learning. | Determining the correlation between study habits and exam scores. |

| Health Psychology | Exploring links between psychological factors and physical health. | Analyzing the correlation between stress levels and immune system function. |

| Industrial-Organizational Psychology | Predicting job performance and employee satisfaction. | Studying the correlation between leadership style and team productivity. |

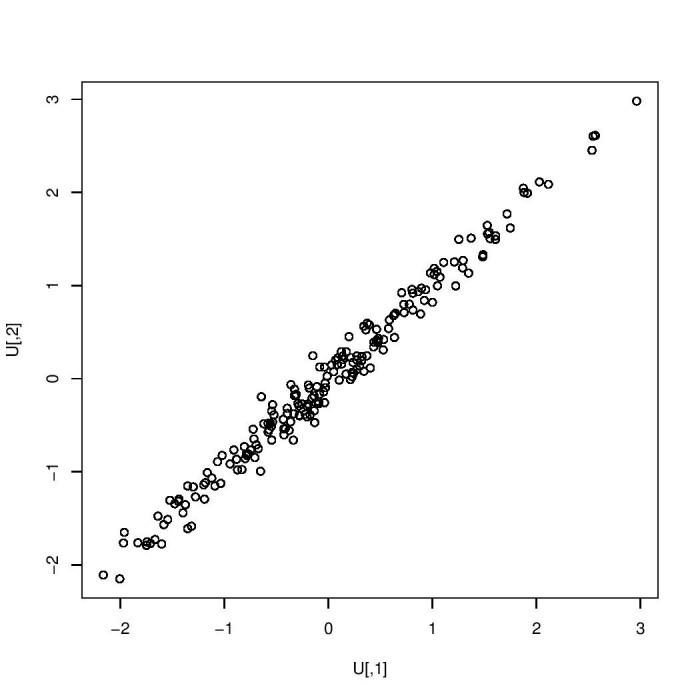

Visualizing Correlational Data

Just as a wise teacher uses diagrams to make complex ideas clear, psychologists use visual tools to understand the relationships between different psychological factors. These pictures help us see patterns that might be hard to spot in raw numbers alone, allowing us to grasp the nature and strength of connections.One of the most powerful tools for visualizing correlational data is the scatterplot.

This graphical representation allows us to plot pairs of values for two variables, revealing the overall trend and the degree to which they are related. By observing the arrangement of these points, we can gain an immediate understanding of the correlation.

Scatterplots for Representing Correlational Relationships

A scatterplot is a graph that displays the relationship between two quantitative variables. Each point on the scatterplot represents a single observation, with its position determined by the values of the two variables being measured. For example, if we are looking at the relationship between hours studied and exam scores, each point would represent one student, showing how many hours they studied and what score they achieved.

The distribution of these points allows us to visually assess if there is a pattern, and what that pattern might be.

Interpreting Scatterplot Patterns

The way the points are arranged on a scatterplot provides crucial information about the correlation. The general direction and spread of the points help us infer both the type and strength of the relationship.

- Direction: If the points generally move from the bottom left to the top right, it suggests a positive correlation. If they move from the top left to the bottom right, it indicates a negative correlation.

- Spread: The tighter the cluster of points around an imaginary line, the stronger the correlation. A wide, dispersed spread suggests a weaker correlation.

Scatterplot for a Strong Positive Correlation

A scatterplot depicting a strong positive correlation would show points that are tightly clustered and form a clear upward trend from left to right. Imagine drawing a straight line through the middle of these points; most of the points would lie very close to this line. As the value of one variable increases, the value of the other variable also tends to increase consistently and predictably.

For instance, if we plotted the height of children against their age (within a certain developmental range), we would expect to see most points forming a tight band moving upwards and to the right, indicating that as children get older, they generally get taller.

Scatterplot for a Strong Negative Correlation

Conversely, a scatterplot showing a strong negative correlation would display points that are also tightly clustered but form a distinct downward trend from left to right. If you were to draw a line through the center of these points, they would closely follow it. In this type of relationship, as the value of one variable increases, the value of the other variable tends to decrease consistently.

An example could be plotting the number of hours spent playing video games per week against academic performance scores. A strong negative correlation would mean that as students spend more hours playing video games, their academic scores tend to be lower, with the points forming a tight, descending line.

Scatterplot for a Weak or Zero Correlation

When a scatterplot shows a weak or zero correlation, the points are widely dispersed and do not form a clear linear pattern. There might be a slight tendency for the points to move in a particular direction, but this trend is very faint, or the points may appear to be scattered randomly across the graph. A weak correlation suggests that the two variables are related, but the relationship is not very predictable.

A zero correlation implies that there is virtually no linear relationship between the two variables; knowing the value of one variable tells us very little about the value of the other. For example, plotting a person’s shoe size against their intelligence quotient would likely result in a scatterplot with points spread out randomly, indicating a near-zero correlation.

Last Point

As we draw the curtain on this exploration, the profound significance of correlation in psychology becomes luminously clear. It is the silent architect behind much of our understanding, a vital tool for deciphering the complex tapestry of human experience. From charting the subtle dance between personality traits and social interactions to predicting potential trajectories in development, correlation offers a powerful lens.

While it whispers of relationships and guides our hypotheses, it also serves as a crucial reminder of the delicate boundary between association and causation, urging us to tread carefully in our pursuit of psychological truths. The quest to understand what is a correlation in psychology is not merely an academic exercise, but a journey into the very interconnectedness of our inner worlds.

FAQs

What is the main goal of studying correlations in psychology?

The primary goal is to understand and describe the strength and direction of the relationship between two or more psychological variables. It helps researchers identify patterns and make predictions, forming the basis for further investigation.

Can correlation tell us if one psychological factor causes another?

No, correlation does not imply causation. While two variables might be strongly related, correlation alone cannot prove that one variable directly influences the other. There could be a third, unmeasured variable influencing both.

What does a correlation coefficient of zero mean?

A correlation coefficient of zero indicates that there is no linear relationship between the two variables being studied. As one variable changes, the other does not show a consistent pattern of change.

How does a scatterplot help in understanding correlation?

A scatterplot visually represents the relationship between two variables by plotting data points. The pattern of these points—whether they form a line, cluster, or are randomly dispersed—allows for a quick assessment of the type and strength of the correlation.

What is the difference between Pearson’s r and Spearman’s rho?

Pearson’s r is used for linear relationships between continuous variables, assuming data is normally distributed. Spearman’s rho is used for ordinal data or when the relationship is monotonic (consistently increasing or decreasing but not necessarily linear), and it’s less sensitive to outliers.