What are variables in psychology sets the stage for this enthralling narrative, offering readers a glimpse into a story that is rich in detail and brimming with originality from the outset. Basically, variables are the building blocks of psychological research, letting us dissect and understand the complex inner workings of the human mind and behavior. Think of them as the ingredients we measure, manipulate, or observe to figure out how things like thoughts, feelings, and actions connect.

From figuring out if more sleep leads to better grades to understanding how stress affects our decision-making, variables are what allow psychologists to turn abstract ideas into testable hypotheses. We’ll dive into how these variables are defined, categorized, and even how we make sure we’re actually measuring what we think we are. It’s all about making sense of the messy, fascinating world of human psychology in a structured, scientific way.

Defining Psychological Variables

In the intricate landscape of psychological research, variables serve as the fundamental building blocks, the observable and measurable aspects that allow us to explore, understand, and predict human behavior and mental processes. Without variables, research would be a nebulous endeavor, lacking the precision and structure necessary to draw meaningful conclusions about the complexities of the mind and its manifestations. They are, in essence, the phenomena we manipulate, measure, or observe to uncover relationships and test hypotheses.At its core, a variable in psychology is any characteristic, attribute, or factor that can vary or take on different values.

These values can be numerical, such as reaction times or scores on a personality test, or categorical, like gender or diagnostic group. The ability of a variable to change is what makes it useful for research; it allows us to compare conditions, identify differences, and establish connections between different psychological constructs. The careful selection and operationalization of variables are paramount to the validity and reliability of any psychological study.

Independent Variables in Psychological Studies

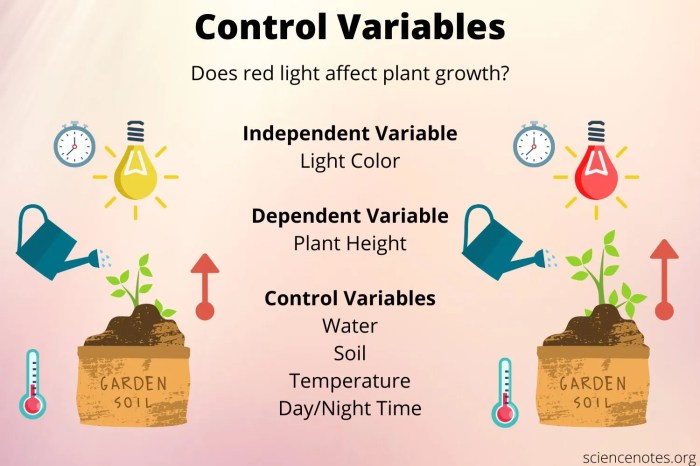

Independent variables (IVs) are the factors that researchers manipulate or change in an experiment to observe their effect on another variable. They are the presumed “causes” in a cause-and-effect relationship. The researcher controls the levels or conditions of the independent variable, exposing different groups of participants to these different conditions or systematically altering the variable itself. This controlled manipulation is crucial for establishing causality, as it helps to isolate the effect of the independent variable from other potential influences.Common independent variables in psychological studies often relate to interventions, environmental conditions, or participant characteristics that are systematically varied.

These can include:

- Type of Therapy: Comparing the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus psychodynamic therapy for depression.

- Dosage of a Medication: Administering different doses of an antidepressant to assess their impact on mood.

- Environmental Stimuli: Exposing participants to different levels of noise to study its effect on concentration.

- Instructional Methods: Teaching students using either a lecture-based approach or an interactive problem-solving method.

- Sleep Deprivation: Varying the number of hours participants are allowed to sleep before a cognitive task.

- Social Presence: Having participants perform a task alone versus in the presence of others.

Dependent Variables in Psychological Research

Dependent variables (DVs) are the outcomes that researchers measure to see if they are affected by the independent variable. They are the presumed “effects” in a cause-and-effect relationship. The researcher does not manipulate the dependent variable; rather, they observe and record changes in it, assuming these changes are a result of the manipulation of the independent variable. The operational definition of a dependent variable is critical, as it dictates precisely how the outcome will be measured, ensuring consistency and replicability.Examples of common dependent variables measured in psychological research reflect the diverse range of phenomena psychologists investigate:

- Behavioral Measures: The number of times a specific behavior occurs (e.g., aggressive acts), the speed of response (e.g., reaction time), or the accuracy of performance on a task.

- Physiological Measures: Heart rate, blood pressure, galvanic skin response (GSR), or brain activity patterns (e.g., EEG, fMRI).

- Self-Report Measures: Scores on questionnaires or surveys assessing mood, anxiety levels, personality traits, or satisfaction.

- Cognitive Performance: Memory recall scores, problem-solving efficiency, or decision-making accuracy.

- Emotional Responses: Ratings of happiness, sadness, fear, or anger.

- Social Interactions: The frequency or quality of communication between individuals.

The Relationship Between Independent and Dependent Variables

The relationship between independent and dependent variables is the cornerstone of experimental research in psychology. It is the hypothesized link that researchers seek to uncover and validate. In a typical experimental design, the independent variable is manipulated, and its subsequent effect on the dependent variable is observed and measured. This allows researchers to infer whether changes in the independent variable cause changes in the dependent variable.

The essence of experimental inquiry lies in the systematic manipulation of the independent variable to observe its predictable influence on the dependent variable.

Consider a study investigating the impact of caffeine intake (independent variable) on reaction time (dependent variable). The researcher might assign participants to one of three groups: one receiving no caffeine, another receiving a moderate dose, and a third receiving a high dose. After a waiting period, all participants complete a reaction time task. The researcher then measures the reaction times of each participant.

If the group receiving higher doses of caffeine exhibits significantly faster reaction times compared to the other groups, this would suggest a causal relationship where caffeine intake influences reaction speed.In non-experimental research, such as correlational studies, the relationship between variables is examined without direct manipulation. Here, researchers measure two or more variables as they naturally occur and assess the degree to which they are associated.

For instance, a study might examine the correlation between hours of study (one variable) and exam scores (another variable). While a strong positive correlation might be found, indicating that more study hours are associated with higher scores, this does not prove causation. Other factors, like innate ability or motivation, could be influencing both variables. Nevertheless, the concept of how one variable might relate to or influence another remains central to the inquiry.

Types of Psychological Variables: What Are Variables In Psychology

Understanding the diverse nature of psychological variables is fundamental to conducting rigorous research and drawing meaningful conclusions. Just as a carpenter needs to know the difference between a nail and a screw, a psychologist must distinguish between the various types of variables they measure. This differentiation allows for the appropriate selection of research designs, statistical analyses, and ultimately, the accurate interpretation of findings.

The primary distinction lies in whether a variable can be broken down into distinct categories or if it exists on a continuum.The classification of psychological variables is intrinsically linked to the scales of measurement used. These scales dictate the mathematical operations that can be performed and the types of conclusions that can be drawn. Recognizing these distinctions is not merely an academic exercise; it directly impacts the validity and utility of psychological research.

Categorical and Continuous Variables, What are variables in psychology

Psychological variables can be broadly categorized into two main types: categorical and continuous. This distinction is crucial for determining the appropriate statistical methods to be employed in analyzing data.Categorical variables, also known as discrete variables, represent distinct groups or categories. An individual or observation can only belong to one category at a time, and there are no values in between.

These categories do not inherently possess a numerical order, although they may be assigned numerical labels for convenience.Continuous variables, on the other hand, can take on any value within a given range. Theoretically, there are an infinite number of possible values between any two given points on the scale. These variables are often measured and can be precisely quantified.

Measurement Scales for Psychological Variables

The way a psychological variable is measured significantly influences the information we can extract from it. Stevens’ levels of measurement provide a framework for understanding these differences, ranging from the simplest to the most sophisticated. Each scale possesses unique properties that determine the types of statistical analyses that are appropriate.The four main scales of measurement are nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio.

- Nominal Scale: This is the most basic level of measurement. Variables measured on a nominal scale are used to categorize or label observations into distinct, non-overlapping groups. There is no inherent order or hierarchy among the categories. Numerical assignments are purely for identification purposes and do not imply magnitude or rank. For example, assigning ‘1’ to male and ‘2’ to female in a survey is nominal.

Other examples include hair color (e.g., brown, blonde, black), political affiliation (e.g., Democrat, Republican, Independent), or diagnostic categories in mental health (e.g., depression, anxiety, schizophrenia).

- Ordinal Scale: This scale involves categories that have a natural order or rank. While the categories can be ordered, the distance between adjacent categories is not necessarily equal or known. For instance, ranking students based on their performance in a class as first, second, or third place is an ordinal measure. The difference in performance between the first and second student might not be the same as the difference between the second and third.

Other examples include Likert scales (e.g., “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”), socioeconomic status (e.g., low, medium, high), or levels of agreement (e.g., never, sometimes, often, always).

- Interval Scale: Variables measured on an interval scale have ordered categories, and the distances between adjacent categories are equal and meaningful. However, interval scales lack a true zero point, meaning that zero does not represent the complete absence of the measured attribute. This limitation prevents us from making ratio comparisons (e.g., saying one value is twice as much as another). A classic example is the Celsius or Fahrenheit temperature scale.

A temperature of 20°C is not twice as hot as 10°C because 0°C does not represent the absence of heat. IQ scores are also often treated as interval data, where the difference between an IQ of 100 and 110 is the same as the difference between 110 and 120, but an IQ of 0 does not mean zero intelligence.

- Ratio Scale: This is the highest level of measurement. Ratio scales possess all the properties of interval scales (ordered categories, equal intervals) and also have a true zero point. This true zero signifies the complete absence of the quantity being measured, allowing for meaningful ratio comparisons. For example, height, weight, reaction time, or the number of correct answers on a test are all measured on a ratio scale.

If someone is 180 cm tall and another is 90 cm tall, the first person is indeed twice as tall as the second. Similarly, a reaction time of 500 milliseconds is twice as long as 250 milliseconds.

Discrete and Continuous Variables in Psychology

The distinction between discrete and continuous variables is fundamental to understanding how psychological phenomena are quantified and analyzed. This differentiation impacts the types of statistical models that can be applied and the interpretations that can be made about the data.Discrete variables are those that can only take on a finite number of values or a countably infinite number of values.

They often arise from counting or categorization. In psychology, discrete variables typically represent distinct categories or whole numbers.Continuous variables, conversely, can theoretically take on any value within a given range. They are often the result of measurement and can be infinitely subdivided. In psychological research, continuous variables represent phenomena that exist on a spectrum.

| Variable Type | Definition | Psychological Examples | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrete | Can only take on specific, separate values; often whole numbers. | Number of errors on a test, number of therapy sessions attended, number of children in a family. | Countable, distinct values, no values in between. |

| Categorical variables are a type of discrete variable. | Gender (male, female, non-binary), ethnicity (e.g., Caucasian, Asian, Hispanic), marital status (single, married, divorced). | Categories, no inherent numerical value or order (nominal) or ordered categories with unequal intervals (ordinal). | |

| Continuous | Can take on any value within a given range; theoretically infinite values. | Height, weight, reaction time, score on an anxiety inventory. | Measurable, can be precisely quantified, values can be fractional. |

| Interval and ratio scales measure continuous variables. | Temperature (Celsius/Fahrenheit), age, duration of sleep, scores on standardized intelligence tests. | Equal intervals between values, may or may not have a true zero point. |

Scenarios Illustrating Measurement Scales

To solidify the understanding of measurement scales, consider the following scenarios that demonstrate their application to common psychological constructs. These examples highlight how the nature of the construct and the research question dictate the appropriate scale of measurement.Scenario 1: Measuring Anxiety LevelsA researcher wants to assess the anxiety levels of participants before a public speaking event.

- Nominal: Participants could be classified as “Anxious” or “Not Anxious” based on a simple yes/no question. This is a binary nominal variable.

- Ordinal: Participants could rate their anxiety on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 = “Not at all anxious” and 5 = “Extremely anxious.” This ordinal scale indicates a rank order of anxiety but not the precise difference in intensity between levels.

- Interval: A standardized anxiety questionnaire, such as the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), provides scores that are treated as interval data. The difference between a score of 30 and 40 is considered equivalent to the difference between 40 and 50, assuming the test is well-constructed and validated. However, a score of 0 on the STAI does not mean zero anxiety.

- Ratio: While difficult to measure directly, a physiological indicator like the duration of a specific stress-related physiological response (e.g., cortisol release time) could theoretically be measured on a ratio scale, with a true zero point representing the absence of that response.

Scenario 2: Assessing Social SupportA psychologist is investigating the impact of social support on well-being.

- Nominal: Participants could be categorized by their primary source of social support, such as “Family,” “Friends,” or “Colleagues.”

- Ordinal: Participants could rank the importance of different sources of social support (e.g., “Most important,” “Second most important,” “Third most important”).

- Interval: A social support questionnaire might yield a total score where higher scores indicate greater perceived social support. These scores are often treated as interval data, allowing for comparisons of differences in support levels.

- Ratio: The number of close confidants a person reports having could be a ratio variable. If someone reports having 4 confidants and another reports 2, the first person has twice as many confidants.

Scenario 3: Evaluating Learning OutcomesAn educational psychologist is evaluating the effectiveness of a new teaching method.

- Nominal: Students could be assigned to either the “New Method” group or the “Traditional Method” group.

- Ordinal: Students could be ranked based on their engagement with the material, from “Least Engaged” to “Most Engaged.”

- Interval: Scores on a post-test designed to measure knowledge acquisition could be treated as interval data. The difference in knowledge between a score of 70 and 80 is assumed to be the same as between 80 and 90.

- Ratio: The number of correct answers on a multiple-choice quiz represents a ratio scale. If one student gets 10 correct answers and another gets 5, the first student has answered twice as many questions correctly. A score of 0 correct answers means no questions were answered correctly.

Operationalizing Psychological Variables

The transition from abstract psychological constructs to concrete, measurable phenomena is a cornerstone of empirical psychological research. This process, known as operationalization, is what imbues subjective experiences with scientific rigor, allowing for systematic observation, comparison, and analysis. Without it, psychological concepts would remain the realm of philosophical speculation rather than testable hypotheses. It is the bridge that connects theory to data, enabling us to ask and answer questions about the human mind and behavior in a quantifiable way.Operationalization involves defining a variable in terms of the specific procedures or operations used to measure or manipulate it.

This ensures that different researchers, when studying the same concept, are referring to and measuring the same thing, thereby enhancing the reliability and validity of their findings. It requires careful consideration of what aspects of a concept can be observed and quantified, and how best to capture those aspects.

Defining Operational Definitions

An operational definition specifies the precise steps and criteria used to measure or manipulate a concept. It is not a statement of what the concept

- is* in an absolute sense, but rather

- how* it will be observed and quantified within a particular study. This specificity is crucial for replicability, allowing other researchers to repeat the study exactly as described or to compare their results with the original findings. For instance, while “happiness” is a complex emotion, an operational definition might specify it as a score on a particular self-report questionnaire.

Anxiety Operationalization for Test Performance

Operationalizing ‘anxiety’ for a study on test performance requires defining observable and measurable indicators that reflect the subjective experience of anxiety in the context of an academic assessment. These indicators must be distinct and quantifiable.Consider a study examining the relationship between anxiety and performance on a standardized mathematics test. An operational definition for anxiety could involve a multi-faceted approach:

- Physiological Measures: Heart rate (beats per minute), skin conductance (measured in microsiemens), and respiration rate (breaths per minute) could be recorded during the test. Elevated levels in these measures would indicate physiological arousal associated with anxiety.

- Self-Report Measures: Participants could complete a validated anxiety questionnaire, such as the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) or the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), immediately before and after the test. Scores on these inventories would serve as a direct measure of subjective anxiety.

- Behavioral Observations: Researchers could observe and code specific behaviors during the test, such as fidgeting, nail-biting, or avoidance behaviors (e.g., looking away from the test for extended periods). The frequency or duration of these behaviors could be quantified.

The chosen operational definition would specify which of these measures are used and how they are combined or analyzed. For example, an operational definition might state: “Anxiety will be operationalized as the average heart rate during the test and the score on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) administered immediately before the test.”

Intelligence Operationalization for Cognitive Assessment

Operationalizing ‘intelligence’ for a cognitive assessment involves translating this broad construct into specific, measurable cognitive abilities that can be evaluated through standardized tests. Given that intelligence is not a singular entity, operational definitions often focus on specific facets or a composite of various cognitive functions.For a cognitive assessment, intelligence could be operationalized through performance on a battery of standardized tests designed to measure different cognitive domains.

Examples include:

- Verbal Comprehension: Measured by subtests such as vocabulary, similarities, and comprehension from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) or the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales.

- Perceptual Reasoning: Assessed through tasks like block design, matrix reasoning, and visual puzzles, which evaluate non-verbal problem-solving and spatial abilities.

- Working Memory: Quantified by tasks requiring the manipulation and retention of information, such as digit span or arithmetic subtests.

- Processing Speed: Measured by timed tasks like symbol search or coding, which assess how quickly individuals can perform simple cognitive operations.

The overall operational definition of intelligence for the assessment would typically be the composite score derived from these subtests, often standardized to an intelligence quotient (IQ) score. For instance, a study might define intelligence as: “Intelligence will be operationalized as the full-scale IQ score obtained from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-IV (WAIS-IV).”

Potential Operational Definitions for Stress and Suitability Evaluation

Operationalizing ‘stress’ presents a similar challenge to other psychological variables, as it encompasses physiological, cognitive, and behavioral responses. A variety of definitions can be employed, each with its own strengths and limitations depending on the research question.Here is a set of potential operational definitions for ‘stress’ and an evaluation of their suitability:

- Definition 1: Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) Score

- Description: Participants complete the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), a 10-item questionnaire that measures the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as stressful. Scores range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater perceived stress.

- Suitability: Highly suitable for studies focusing on subjective experience and cognitive appraisal of stressors. It is widely used, easy to administer, and cost-effective. However, it relies on self-report and may be influenced by response biases.

- Definition 2: Cortisol Levels in Saliva

- Description: Salivary cortisol samples are collected at multiple time points (e.g., upon waking, midday, evening) over a period of days. Elevated cortisol levels, particularly a blunted diurnal rhythm, are indicative of chronic stress.

- Suitability: Provides an objective, physiological measure of the body’s stress response system (the HPA axis). It is less susceptible to conscious bias. However, collecting samples can be intrusive, and cortisol levels can be influenced by numerous factors other than psychological stress (e.g., medication, time of day, physical activity).

- Definition 3: Number of Life Events in the Past Year

- Description: Participants complete a checklist of significant life events (e.g., job loss, divorce, death of a loved one) that have occurred within the last 12 months, often weighted by their severity using scales like the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS).

- Suitability: Useful for examining the impact of major life changes. It captures external stressors. However, it does not account for individual differences in coping or appraisal, nor does it measure ongoing daily hassles, which can also be significant stressors. It also relies on retrospective recall, which can be inaccurate.

- Definition 4: Blood Pressure and Heart Rate During a Stressor Task

- Description: Physiological measures such as systolic and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate are recorded before, during, and after a standardized laboratory stressor, such as a public speaking task or a difficult cognitive challenge (e.g., Stroop test).

- Suitability: Offers a direct, real-time measure of the body’s acute physiological response to a specific stressor. It is objective and can reveal immediate reactions. However, it only captures short-term responses to specific laboratory-induced stressors and may not generalize to chronic or real-world stress.

The most suitable operational definition for stress will depend entirely on the research question. For instance, if the study aims to understand how individualsperceive* the stressfulness of their daily lives, the PSS would be ideal. If the focus is on the physiological impact of chronic stress, cortisol levels might be preferred. For examining the immediate impact of a specific event, physiological measures during a task would be more appropriate.

Often, researchers use a combination of these definitions to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of stress.

Controlling and Manipulating Variables

In the rigorous pursuit of understanding psychological phenomena, the ability to control and manipulate variables stands as a cornerstone of robust scientific inquiry. Without careful management of these elements, the conclusions drawn from research can be clouded by ambiguity, making it difficult to establish clear cause-and-effect relationships. This section delves into the critical practices of controlling extraneous influences and deliberately altering independent variables to illuminate the intricate workings of the human mind and behavior.The fundamental aim of experimental research in psychology is to isolate the impact of one or more variables on another.

This requires a meticulous approach to ensure that only the intended variables are influencing the outcome, thereby safeguarding the validity of the findings.

Controlling Extraneous Variables

Extraneous variables, often referred to as confounding variables, pose a significant threat to the internal validity of a study. These are factors that could potentially influence the dependent variable, but are not the independent variable of interest. If left uncontrolled, they can lead researchers to incorrectly attribute observed effects to the independent variable when, in reality, they are due to these lurking influences.

Imagine a study on the effects of a new teaching method on student performance. If students in the experimental group also happen to have a more experienced teacher, or if they receive more individual attention outside of the study, these factors become extraneous variables that could inflate their performance, making the new teaching method appear more effective than it truly is.

Therefore, identifying and mitigating these variables is paramount for drawing accurate conclusions.Methods for controlling confounding variables are diverse and depend heavily on the research design and the specific variables under investigation. In a study examining the impact of sleep deprivation on memory recall, for instance, several extraneous variables must be managed.

- Participant Selection and Random Assignment: Ensuring that participants are randomly assigned to different conditions (e.g., sleep-deprived vs. well-rested) helps to distribute potential confounding factors, such as baseline memory ability, motivation levels, or general health, evenly across groups. This minimizes the likelihood that pre-existing differences between participants will systematically affect the outcome.

- Standardized Procedures: All aspects of the experimental procedure, from the instructions given to participants to the environment in which the study is conducted, should be identical for all groups, except for the manipulation of the independent variable. For the sleep deprivation study, this would include standardizing the testing environment (lighting, noise levels) and the timing of the memory recall task.

- Controlling Environmental Factors: External stimuli that could interfere with memory recall, such as unexpected noises or interruptions, must be minimized. The testing rooms should be quiet and free from distractions.

- Controlling for Time of Day: Cognitive performance can vary throughout the day. If the study involves testing participants at different times, it is important to standardize this or at least record it as a potential covariate. For instance, all participants might be tested in the morning.

- Controlling for Prior Knowledge: If the memory task involves specific information, researchers should ensure that participants do not have prior exposure to this information, or at least measure and account for any pre-existing knowledge.

Manipulating the Independent Variable

The deliberate alteration of an independent variable is the defining characteristic of an experiment. This manipulation allows researchers to observe whether changes in the independent variable lead to predictable changes in the dependent variable. In social psychology, experiments often involve manipulating social situations or stimuli to understand their effects on behavior.For a social psychology experiment investigating the effect of group size on bystander intervention in an emergency situation, the independent variable would be the size of the group present when the emergency occurs.

Procedures for manipulating this independent variable could involve creating simulated emergency scenarios in a controlled laboratory setting or a carefully orchestrated field experiment. Participants would be led to believe they are part of a different study, perhaps a survey or a task unrelated to emergencies.

- Creating Different Group Sizes: Researchers would set up distinct conditions representing different group sizes. For example:

- Condition 1 (Alone): The participant believes they are the only one present when the emergency occurs.

- Condition 2 (Small Group): The participant is part of a small group (e.g., 3-4 confederates – individuals working with the experimenter – who are instructed to behave passively).

- Condition 3 (Large Group): The participant is part of a larger group (e.g., 8-10 confederates, also instructed to be passive).

The confederates’ consistent behavior is crucial for isolating the effect of the participant’s own perception of the group size.

- Simulating the Emergency: A believable emergency situation would be staged. This could involve a staged accident, a smoke alarm sounding, or a person appearing to be in distress. The nature and severity of the emergency should be consistent across all conditions.

- Measuring the Dependent Variable: The primary dependent variable would be the likelihood and speed of bystander intervention. This could be measured by observing whether the participant reports the emergency, attempts to help, or expresses concern.

- Debriefing: After the experiment, participants must be thoroughly debriefed about the true nature of the study, the deception involved, and the importance of their participation. This is a critical ethical step in social psychology research.

Experimental Manipulation Versus Correlational Approaches

The relationship between experimental manipulation and correlational approaches to studying variables is a fundamental distinction in psychological research methodology. Both aim to understand how variables relate, but they differ significantly in their ability to infer causality.Experimental manipulation involves actively changing the independent variable and observing its effect on the dependent variable, while holding other factors constant. This direct intervention allows researchers to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

For example, if an experiment shows that participants who receive a specific type of therapy (independent variable) exhibit a significant reduction in anxiety symptoms (dependent variable) compared to a control group, the researcher can confidently conclude that the therapy caused the reduction in anxiety.

In psychology, variables are key to understanding behavior, and one crucial area of study is how can a patient be psychologically influenced by others attitudes. These external attitudes, acting as significant variables, can profoundly shape a patient’s internal state, demonstrating how environmental factors are vital variables in psychological research.

“Experimental manipulation is the gold standard for establishing causality because it involves active intervention and control over extraneous variables.”

Correlational approaches, on the other hand, examine the statistical relationship between two or more variables as they naturally occur. Researchers measure variables without manipulating them. For instance, a study might investigate the correlation between the number of hours students spend studying and their exam scores. If a positive correlation is found (i.e., more study hours are associated with higher scores), it suggests a relationship, but it does not prove causation.

Several reasons explain why correlation does not equal causation:

- Third Variable Problem: A third, unmeasured variable might be responsible for the relationship between the two observed variables. In the study hours/exam scores example, a third variable like inherent academic ability or motivation could influence both study habits and exam performance.

- Directionality Problem: It may be unclear which variable is influencing the other. Does studying more lead to better grades, or do students who get better grades tend to study more because they enjoy the subject or are more confident?

While correlational studies cannot establish causality, they are invaluable for identifying potential relationships, generating hypotheses for experimental testing, and studying variables that cannot be ethically or practically manipulated (e.g., the effects of trauma, personality traits). They are often the first step in understanding complex phenomena, paving the way for more controlled experimental investigations.

Measuring Psychological Variables

The precise measurement of psychological variables is the bedrock upon which robust psychological research and practice are built. Without accurate and consistent tools, our understanding of human behavior and mental processes would be speculative at best. This section delves into the critical concepts of reliability and validity, the twin pillars of sound measurement, and surveys common instruments used to quantify psychological constructs.The journey of measuring psychological variables hinges on two fundamental qualities: reliability and validity.

Reliability speaks to the consistency and stability of a measurement tool. If a scale consistently produces similar results under similar conditions, it is considered reliable. Conversely, validity addresses the accuracy of the measurement – does it truly measure what it purports to measure? A reliable tool may not be valid, but a valid tool must inherently be reliable.

Reliability in Psychological Measurement

Reliability in psychological measurement refers to the degree to which a measure is consistent and free from random error. A reliable instrument will produce similar results when administered repeatedly to the same individuals, provided the underlying construct being measured has not changed. This consistency is crucial for building confidence in the findings derived from the measurement.

Types of Reliability

Several types of reliability are assessed to ensure a psychological instrument is dependable:

- Test-Retest Reliability: This assesses the stability of a measure over time. The same test is administered to a group of participants on two separate occasions, and the correlation between the scores from both administrations is calculated. A high correlation indicates good test-retest reliability. For instance, a personality inventory designed to measure introversion should yield similar scores for an individual if taken a month apart, assuming no significant life events have altered their disposition.

- Internal Consistency Reliability: This type of reliability assesses the extent to which different items within a single measure are consistent with each other. It is particularly relevant for multi-item scales. Common methods include:

- Cronbach’s Alpha: This is the most frequently used statistic for internal consistency. It represents the average of all possible split-half reliabilities. A higher Cronbach’s alpha (typically above .70) suggests that the items are measuring the same underlying construct.

For example, a depression questionnaire with several items assessing feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and loss of interest should show high internal consistency if all items are indeed tapping into the core construct of depression.

- Split-Half Reliability: The items of a test are divided into two halves (e.g., odd-numbered items versus even-numbered items), and the scores on the two halves are correlated. A correction formula (like the Spearman-Brown prophecy formula) is often applied to estimate the reliability of the whole test.

- Cronbach’s Alpha: This is the most frequently used statistic for internal consistency. It represents the average of all possible split-half reliabilities. A higher Cronbach’s alpha (typically above .70) suggests that the items are measuring the same underlying construct.

- Inter-Rater Reliability: This is important when the measurement involves subjective judgment or observation by multiple raters. It assesses the degree of agreement between two or more independent raters. For example, if two psychologists are observing children’s aggressive behaviors on a playground, their ratings should be highly correlated to ensure the observational scheme is being applied consistently. Cohen’s kappa or intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) are common statistics used here.

Validity in Psychological Measurement

Validity refers to the extent to which a measurement tool accurately measures the psychological construct it is intended to measure. It is the most critical aspect of measurement, as an unreliable measure can at least be improved, but an invalid measure provides fundamentally flawed data.

Types of Validity

There are several types of validity that researchers consider:

- Construct Validity: This is the overarching type of validity, concerned with whether the instrument measures the theoretical construct it is designed to measure. It involves a broader evaluation of the evidence supporting the interpretation of the scores.

- Convergent Validity: Evidence that the measure correlates highly with other measures of the same or similar constructs. For instance, a new measure of anxiety should correlate strongly with existing, well-established measures of anxiety.

- Discriminant (or Divergent) Validity: Evidence that the measure does not correlate highly with measures of theoretically unrelated constructs. A measure of anxiety, for example, should not correlate highly with a measure of intelligence.

- Criterion-Related Validity: This type of validity assesses how well a measure predicts or correlates with an external criterion.

- Predictive Validity: The extent to which a measure predicts future outcomes. For example, college entrance exam scores have predictive validity if they accurately predict students’ future academic performance.

- Concurrent Validity: The extent to which a measure correlates with a criterion measure obtained at the same time. For instance, a new, brief measure of depression should correlate highly with a longer, established depression inventory administered concurrently.

- Content Validity: This refers to the extent to which the items on a test or measure adequately represent all the important aspects of the construct being measured. It is often assessed by expert judgment. For example, a final exam in a statistics course should cover all the major topics taught during the semester to have good content validity.

Common Psychological Measurement Tools and Variables

A variety of tools are employed in psychology to measure different constructs. The choice of tool depends on the specific variable of interest and the research question.

| Measurement Tool | Primary Variables Assessed | Examples of Application |

|---|---|---|

| Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) | Personality traits, psychopathology (e.g., depression, schizophrenia, paranoia) | Clinical diagnosis, forensic evaluations, personnel selection. |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | Severity of depressive symptoms | Assessing depression in clinical and research settings, monitoring treatment effectiveness. |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | Anxiety (state anxiety – temporary feeling; trait anxiety – general disposition) | Measuring anxiety levels in response to stressors, assessing generalized anxiety. |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) | General intelligence (IQ), cognitive abilities (e.g., verbal comprehension, perceptual reasoning) | Assessing intellectual functioning, identifying learning disabilities, neuropsychological assessment. |

| Big Five Inventory (BFI) | The five broad personality traits (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism) | Personality research, understanding individual differences in behavior. |

| Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) | Behavioral and emotional problems in children and adolescents | Screening for behavioral disorders, assessing treatment progress. |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | Global self-worth and self-acceptance | Measuring levels of self-esteem in various populations. |

Ethical Considerations in Variable Handling

Navigating the complex landscape of psychological research demands a steadfast commitment to ethical principles, particularly when defining, manipulating, and measuring variables. Researchers must tread carefully, ensuring that their pursuit of knowledge does not compromise the well-being, dignity, or rights of their participants. This ethical compass guides every decision, from the initial conceptualization of a study to the final dissemination of findings.The very act of studying human behavior involves interacting with individuals whose internal states and observable actions are the focus.

Therefore, the ethical handling of variables is not merely a procedural step but a foundational element of responsible scientific inquiry. It underscores the respect due to each person who contributes to our understanding of the human psyche.

Ethical Guidelines for Researchers in Variable Handling

Researchers are bound by a stringent set of ethical guidelines to ensure the integrity and humaneness of their studies, especially concerning variables. These principles, often codified by professional organizations like the American Psychological Association (APA) or the British Psychological Society (BPS), serve as a framework for responsible conduct. They emphasize the paramount importance of participant welfare, scientific validity, and professional integrity.Key ethical considerations include:

- Beneficence and Non-Maleficence: Researchers must strive to maximize potential benefits for participants and society while minimizing any potential harm. This involves carefully weighing the risks associated with manipulating or measuring variables against the expected scientific gains.

- Fidelity and Responsibility: Establishing trust and maintaining professional relationships are crucial. Researchers must be honest, uphold their commitments, and avoid conflicts of interest that could compromise their judgment in variable handling.

- Integrity: Scientists must promote accuracy, honesty, and truthfulness in their research. This means accurately representing variables, avoiding fabrication or falsification of data, and transparently reporting methods, including how variables were defined and measured.

- Justice: The benefits and burdens of research should be distributed fairly across different populations. Researchers must ensure that selection of participants for studies involving specific variables is equitable and that no group is unduly exploited or excluded without good reason.

- Respect for People’s Rights and Dignity: This fundamental principle encompasses respecting the autonomy of individuals, protecting vulnerable populations, and maintaining privacy and confidentiality. When dealing with sensitive variables, extra precautions are necessary.

Informed Consent for Variable Measurement and Manipulation

Informed consent is a cornerstone of ethical research, acting as a vital safeguard for participants. When variables are to be measured or manipulated, it is imperative that individuals understand what this entails and freely agree to participate. This process ensures that participants are not merely subjects but active collaborators in the research endeavor.The informed consent process must clearly articulate:

- The purpose of the study and the specific variables being investigated.

- How these variables will be measured or manipulated, including any potential discomfort or risks associated with these procedures. For example, if a study involves measuring stress levels through physiological means like cortisol sampling, participants must be informed about the collection process and any potential minor discomfort.

- The expected duration of participation.

- Any potential benefits of the research, both for the participant and for society.

- The procedures in place to ensure privacy and confidentiality of the data collected on these variables.

- The participant’s right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

A clear explanation of how sensitive variables will be handled is particularly important. For instance, if a study is examining personality traits linked to social stigma, participants must understand how this information will be stored and reported to ensure their anonymity.

Ethical Implications of Deception in Operationalizing Variables

Deception, while sometimes deemed necessary for operationalizing certain psychological variables, carries significant ethical weight. Its use must be carefully considered and justified, as it can undermine trust and potentially cause distress to participants. The principle of minimizing harm is paramount when deception is employed.When deception is considered:

- Justification: Researchers must demonstrate that deception is essential to the study’s validity and that the research question cannot be answered effectively without it. The potential scientific or societal benefits must outweigh the ethical costs.

- Minimizing Harm: The deception should not involve procedures that could cause significant physical or emotional distress. For example, deceiving participants about their performance on a cognitive task is generally less ethically problematic than deceiving them about a serious health condition.

- Debriefing: A thorough debriefing is absolutely essential. This process involves fully explaining the nature of the deception to participants as soon as their participation is complete, revealing the true purpose of the study, and addressing any misconceptions or negative feelings that may have arisen. Researchers should provide resources for participants who may have experienced distress.

- Institutional Review Board (IRB) Approval: Any study involving deception must undergo rigorous review and approval by an IRB or ethics committee. This body ensures that the use of deception is ethically sound and that appropriate safeguards are in place.

For instance, in studies examining implicit biases, participants might be led to believe the study is about reaction times to images, when in reality, it is measuring their associations between different demographic groups and positive or negative attributes. The debriefing must carefully explain the true nature of the study and offer participants an opportunity to learn about their own potential biases in a non-judgmental way.

Best Practices for Ensuring Participant Privacy and Confidentiality

Protecting participant privacy and confidentiality is a non-negotiable ethical imperative, especially when dealing with sensitive psychological variables. The trust participants place in researchers is predicated on the assurance that their personal information will be handled with the utmost care and discretion. Breaches in privacy can have profound negative consequences for individuals and damage the credibility of psychological research.Best practices include:

- Anonymization and De-identification: Whenever possible, data should be collected and stored anonymously, meaning no identifying information is linked to the responses. If direct identification is necessary for longitudinal studies or specific analyses, data should be de-identified as soon as possible by removing direct identifiers like names and addresses and replacing them with codes.

- Secure Data Storage: Sensitive data must be stored in secure, password-protected systems with limited access. Physical records should be kept in locked cabinets in secure locations. Researchers must be aware of and comply with data protection regulations relevant to their jurisdiction.

- Confidentiality Agreements: All research personnel who have access to participant data should sign confidentiality agreements, underscoring their legal and ethical obligation to protect sensitive information.

- Limited Data Access: Access to identifiable data should be restricted to only those researchers who absolutely require it for their specific tasks. This minimizes the risk of accidental disclosure.

- Reporting Aggregated Data: Findings should always be reported in aggregated form, ensuring that individual responses cannot be identified. Even when reporting qualitative data, pseudonyms should be used, and identifying details should be altered or omitted. For example, in a study on the experiences of individuals with a rare mental health condition, care must be taken to ensure that case descriptions do not inadvertently reveal the identity of any participant, even if pseudonyms are used.

- Data Destruction Policies: Researchers should have clear policies for the secure destruction of identifiable data once it is no longer needed for the research, in accordance with ethical guidelines and institutional policies.

Representing Variable Relationships

Understanding how psychological variables interact is fundamental to building theories and drawing meaningful conclusions from research. This involves not only identifying that a relationship exists but also quantifying its nature and strength. The way we represent these relationships can range from simple numerical summaries to complex visual displays, each offering a unique perspective on the data.The choice of representation depends heavily on the types of variables involved and the research question being addressed.

Continuous variables, which can take on any value within a range, often lend themselves to more nuanced graphical and numerical descriptions of their associations compared to categorical variables.

Representing Continuous Variable Relationships with a Table

A basic yet effective way to illustrate the potential relationship between two continuous psychological variables is through a simple table. This format can present paired data points, allowing for a direct comparison of values. While not as visually intuitive as a graph, it serves as a foundational element for understanding the underlying data.

| Study Hours (X) | Exam Score (Y) |

|---|---|

| 2 | 65 |

| 4 | 78 |

| 6 | 85 |

| 8 | 92 |

| 10 | 95 |

This table shows hypothetical data where an increase in study hours is associated with an increase in exam scores. Each row represents a single observation or participant, linking their reported study hours to their resulting exam score.

Graphical Representations of Variable Associations

Visualizing relationships between variables is crucial for quickly grasping patterns and trends that might be less obvious in raw data or tables. Various graphical methods are employed in psychology to depict these associations, each suited for different types of data and research questions.The following are common graphical representations used to illustrate variable associations in psychology:

- Scatterplots: Ideal for showing the relationship between two continuous variables. Each point on the plot represents an individual observation, with its position determined by the values of the two variables.

- Line Graphs: Often used to display changes in a variable over time or to illustrate how one variable affects another in a sequential manner. They are particularly useful for showing trends.

- Bar Charts: Primarily used for categorical variables, bar charts can show the mean or frequency of a variable across different groups. While not directly showing relationships between continuous variables, they can illustrate differences in a continuous variable across categories.

- Box Plots: Useful for visualizing the distribution of a continuous variable across different categories. They show the median, quartiles, and potential outliers, allowing for comparisons between groups.

Numerical Description of Variable Relationships

Correlation coefficients provide a concise numerical summary of the linear relationship between two continuous variables. They quantify both the strength and the direction of the association, offering a standardized measure that can be compared across different studies.

The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) ranges from -1 to +A value of +1 indicates a perfect positive linear relationship, meaning as one variable increases, the other increases proportionally. A value of -1 indicates a perfect negative linear relationship, where as one variable increases, the other decreases proportionally. A value of 0 suggests no linear relationship between the variables. The absolute value of ‘r’ indicates the strength of the relationship: values closer to 1 (either positive or negative) indicate a stronger relationship, while values closer to 0 indicate a weaker relationship.

Visualizing the Association between Study Hours and Exam Scores with a Scatterplot

A scatterplot is an excellent tool for visually representing the relationship between two continuous variables like ‘study hours’ and ‘exam scores’. It allows researchers and observers to see at a glance if there is a trend, its direction, and its general strength.Imagine a scatterplot where the horizontal axis (x-axis) represents ‘study hours’ and the vertical axis (y-axis) represents ‘exam scores’.

Each participant in a study would be represented by a single dot on this graph. The position of the dot is determined by how many hours that participant studied and what score they achieved on the exam.If, for example, most of the dots cluster around a line that slopes upwards from left to right, this visually depicts a positive correlation.

This means that as the number of study hours increases (moving right on the x-axis), the exam scores also tend to increase (moving up on the y-axis). If the dots were spread out widely, it would suggest a weak relationship, even if there’s a general upward trend. Conversely, a downward sloping trend would indicate a negative correlation, where more study hours are associated with lower scores (which would be an unexpected but possible finding to investigate).

The tightness of the cluster of dots around this trend line indicates the strength of the relationship; a tight cluster signifies a strong relationship, while a dispersed cluster indicates a weak one.

Final Conclusion

So, to wrap things up, variables are the absolute backbone of pretty much all psychological research. Whether we’re talking about what we’re messing with (independent variables) or what we’re watching change (dependent variables), understanding how they work, how to measure them accurately, and how to handle them ethically is key. It’s how we move from guessing to knowing, shedding light on the intricate tapestry of human experience.

Keep an eye out for these concepts, because once you start noticing them, you’ll see them everywhere in the world of psychology.

Helpful Answers

What’s the difference between an independent and dependent variable in simple terms?

Think of it like this: the independent variable is what the researcher changes or manipulates, kind of like the cause. The dependent variable is what’s measured to see if it’s affected by that change, like the effect.

Can you give an example of a categorical variable?

Sure! Gender (male, female, non-binary) or type of therapy (CBT, psychodynamic, none) are good examples. You can sort people into distinct groups, but you can’t really put them on a number line.

What does it mean to “operationalize” a variable?

It means taking a big, abstract idea, like “happiness,” and defining it in a way that you can actually measure in a study. For example, happiness might be operationalized as a score on a specific happiness questionnaire or the number of times someone smiles in an hour.

Why is controlling “extraneous” variables so important?

Extraneous variables are those other factors that could mess with your results. If you don’t control them, you might think your independent variable caused a change, when really it was something else entirely. It’s like trying to see if fertilizer helps plants grow, but forgetting that some plants also got way more sunlight – that extra sun is an extraneous variable.

What’s the deal with reliability and validity in measurement?

Reliability is about consistency: if you measure something multiple times, do you get similar results? Validity is about accuracy: are you actually measuring what you think you’re measuring? You can have a reliable test that’s not valid, but a valid test generally needs to be reliable too.