What is a conditioned response in psychology, a concept deeply rooted in understanding how we learn and adapt? This exploration delves into the fascinating ways our behaviors and even our emotions become linked to specific cues, often without our conscious awareness. It’s a journey into the mechanics of association, revealing how the world around us shapes our internal landscapes and outward reactions.

At its core, a conditioned response is a learned reaction to a stimulus that was once neutral but has become associated with an unconditioned stimulus. This fundamental principle of behavioral psychology, often exemplified by Ivan Pavlov’s groundbreaking experiments, highlights the power of pairing. Through repeated exposure, a previously neutral trigger can elicit a specific, learned response, demonstrating a profound connection between external events and our internal states.

Defining the Concept

Alright, let’s break down what a conditioned response is, no cap. In the wild world of behavioral psychology, it’s basically a learned reaction. Think of it like your brain going, “Whoa, this thing usually means that thing, so I’m gonna react like it’s that thing.” It’s all about making connections, like binge-watching a show and knowing exactly when the commercial break is coming.The whole magic happens when a stimulus that used to be a total nobody – a neutral stimulus – starts hanging out with a stimulus that already makes you react, the unconditioned stimulus.

After enough of these hangouts, the neutral stimulus starts to pull its own weight and can get you to react all by itself. It’s like when your favorite song comes on the radio; you might not have evenseen* the DJ, but your mood instantly shifts, right? That’s the power of association.

Key Components of Conditioned Response Formation

So, how does this whole learning process actually go down? It’s not rocket science, but it’s pretty fascinating. We’re talking about a few key players that have to be in the right place at the right time for the conditioning to stick. These are the building blocks that make a conditioned response a thing.Here are the main components that are crucial for this learned behavior to form:

- Unconditioned Stimulus (UCS): This is the OG, the one that naturally and automatically triggers a response. Think of it as the “real deal” that gets the ball rolling without any prior learning. For example, a sudden loud noise (UCS) naturally makes you jump.

- Unconditioned Response (UCR): This is the automatic, unlearned reaction to the UCS. It’s what happens without you even trying. So, that jump you make when you hear the loud noise? That’s your UCR.

- Neutral Stimulus (NS): Before conditioning, this stimulus doesn’t cause any particular reaction. It’s like background noise, totally irrelevant. Imagine a specific bell sound that you don’t pay any mind to.

- Conditioned Stimulus (CS): This is the formerly neutral stimulus that, after being paired with the UCS, starts to trigger a learned response. It’s the stimulus that has been “trained” to elicit a reaction. In our example, after repeatedly hearing the bell sound right before the loud noise, the bell itself becomes the CS.

- Conditioned Response (CR): This is the learned reaction to the CS. It’s often very similar, if not identical, to the UCR, but it’s now triggered by the CS alone. So, after the conditioning, hearing the bell sound (CS) might make you jump (CR), even if the loud noise isn’t there anymore.

The whole process can be summed up like this: You start with a natural reflex (UCS -> UCR). Then, you introduce a neutral stimulus right before the UCS (NS + UCS -> UCR). Repeat this enough times, and boom – the neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus that can trigger the response on its own (CS -> CR). It’s like Pavlov’s dogs, but, you know, less drooling and more real-world applications.

The essence of a conditioned response lies in the learned association between a previously neutral stimulus and a naturally occurring stimulus, leading to a predictable behavioral outcome.

Historical Foundations and Key Figures

Before we dive into the nitty-gritty of how our brains get wired, let’s rewind the tape and see who laid the groundwork for understanding conditioned responses. It’s like looking at the OG influencers of psychology, the ones who dropped the knowledge bombs that still echo today.The journey into understanding how we learn through association wasn’t a single “aha!” moment, but rather a slow burn, with brilliant minds chipping away at the puzzle.

Early thinkers flirted with the idea of learned associations, but it was a Russian physiologist who really brought the science to the forefront with some seriously cool, albeit slobbery, experiments.

Ivan Pavlov and His Canine Crew

Enter Ivan Pavlov, a Nobel Prize-winning dude whose name is practically synonymous with classical conditioning. He wasn’t initially trying to crack the code of psychological learning; he was actually studying digestion in dogs. Talk about a happy accident! He noticed that his furry test subjects started salivating not just when they saw food, but also when they heard the lab assistant’s footsteps or saw the food bowl.

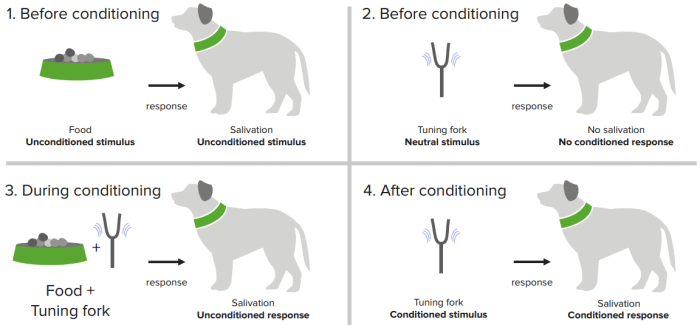

This got him thinking, “Yo, what’s up with that?”Pavlov’s famous experiments involved a dog, a bell (or sometimes a metronome), and some tasty kibble. He’d ring the bell right before presenting the food. Do this a few times, and BAM! The dog would start drooling just at the sound of the bell, even without the food in sight. This wasn’t some magic trick; it was a demonstration of a fundamental learning process.He meticulously documented these findings, identifying key players in this learning drama:

- Unconditioned Stimulus (UCS): This is the real deal, the thing that naturally triggers a response. In Pavlov’s case, it was the food.

- Unconditioned Response (UCR): This is the automatic, unlearned reaction to the UCS. The dog’s salivation to the food is the UCR.

- Neutral Stimulus (NS): This is something that initially doesn’t cause the response. The bell, before conditioning, was just a sound.

- Conditioned Stimulus (CS): After being paired with the UCS, the NS becomes the CS. The bell, after repeated pairings with food, now triggers salivation.

- Conditioned Response (CR): This is the learned response to the CS. The dog salivating at the sound of the bell is the CR.

Pavlov’s groundbreaking work didn’t just make him a legend; it fundamentally changed how we look at learning. He showed us that our environment can powerfully shape our behavior, even in ways we might not consciously realize. His principles of classical conditioning provided a scientific framework for understanding how associations are formed, paving the way for a whole new understanding of the mind.

“The first step in the acquisition of wisdom is to be able to recognize one’s ignorance.”

Ivan Pavlov

Mechanisms of Conditioning

Alright, so we’ve laid the groundwork for what a conditioned response is, tracing its roots and giving props to the OG psychologists. Now, let’s dive into the nitty-gritty, the “how it works” of it all. Think of it like figuring out the cheat codes to the brain’s operating system. It’s all about connections, baby, and how our brains are wired to learn from what’s going down around us.The whole shebang of conditioning hinges on association.

Basically, our brains are like super-detectives, constantly looking for patterns and links between things. When two events happen together repeatedly, our brains start to pair them up. This pairing is the secret sauce that allows us to develop conditioned responses. It’s like when you hear that jingle from your favorite fast-food joint – suddenly, you’re craving a burger, right? That jingle (neutral stimulus) got associated with the deliciousness of the food (unconditioned stimulus), leading to a craving (conditioned response).

The Building Blocks of Learning

To really get a handle on how conditioning works, we gotta break down some key concepts. These are the fundamental processes that explain how we acquire, lose, and then sometimes get back those learned reactions. It’s like understanding the different stages of a video game boss fight – you gotta know the patterns to win.Here’s the lowdown on the essential mechanisms:

- Acquisition: This is the initial stage where the learning actually happens. It’s when the neutral stimulus starts to be paired with the unconditioned stimulus, and the neutral stimulus begins to elicit a response. Think of it as the “aha!” moment when your brain makes the connection. It’s like Pavlov’s dogs first learning that the bell means food is coming.

- Extinction: This is what happens when the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus. The learned association starts to weaken, and the conditioned response eventually fades away. If Pavlov’s dogs kept hearing the bell without any food, they’d eventually stop salivating at the sound. It’s like a favorite TV show getting canceled – the buzz around it eventually dies down.

- Spontaneous Recovery: This is the wild card. Even after extinction, a conditioned response can reappear after a rest period. It’s like that old song you haven’t heard in ages suddenly popping up on shuffle, and you remember all the lyrics and feelings associated with it. The learning isn’t totally gone, just dormant.

- Generalization: This is when the conditioned response is triggered by stimuli that are similar to the original conditioned stimulus. If you learned to fear a specific type of dog because of a bad experience, you might start feeling anxious around all dogs, even those that are friendly. It’s like if your favorite band releases a new song that sounds a lot like their old hits – you’re probably going to like it based on your past experience.

- Discrimination: This is the opposite of generalization. It’s the ability to distinguish between the conditioned stimulus and other similar stimuli, responding only to the original stimulus. A well-trained dog can learn to only come when you say “sit” and not when you say “sit down” or “sit still.” It’s like being able to tell the difference between a perfectly brewed cup of coffee and one that’s just okay.

Generalization vs. Discrimination: Two Sides of the Same Coin

These two processes, stimulus generalization and stimulus discrimination, are super important because they show how flexible and precise our learned responses can be. They’re like the yin and yang of associative learning, shaping how we react to the world around us.Stimulus generalization is all about broad strokes. It’s when a learned response to one stimulus gets applied to similar stimuli.

Imagine you’re a kid and you get stung by a bee. You might develop a fear of all flying insects, not just bees. Your brain is casting a wide net, assuming anything that looks or acts a bit like the scary thing is also scary. This can be helpful for survival, as it allows us to avoid potential dangers that resemble past threats.On the flip side, stimulus discrimination is about fine-tuning.

It’s the ability to tell the difference between the conditioned stimulus and other, similar stimuli. If you’ve learned to salivate at the sound of a specific bell, discrimination means youwon’t* salivate at the sound of a doorbell or a phone ringing, even though they are also sounds. This is crucial for navigating complex environments and making accurate predictions. Without discrimination, our responses would be all over the place, leading to a lot of unnecessary fear or anticipation.

It’s the difference between recognizing your best friend in a crowd and mistaking a stranger for them.

The power of conditioning lies in its ability to create flexible yet precise behavioral responses through the intricate dance of association, extinction, recovery, generalization, and discrimination.

Types of Conditioned Responses

Alright, so we’ve talked about what a conditioned response is and how it all went down historically. Now, let’s dive into the nitty-gritty of what these responses actually look like. Turns out, they’re not all just Pavlov’s dogs drooling at the bell. Conditioned responses can show up in all sorts of wild and wonderful ways, across pretty much every living thing you can think of, and in situations from your everyday grind to, well, anything.These responses can be as subtle as a twitch or as dramatic as a full-blown panic attack.

They can affect how we feel, how our bodies work, and what we do. It’s like our brains are constantly learning and reacting, setting up these automatic triggers that can really shape our experiences.

Conditioned Emotional Responses

Get ready for some feels, because emotions are a huge part of the conditioned response game. Think about it: how many times have you heard a song and suddenly you’re transported back to a specific moment, feeling all the feels associated with it? That’s your conditioned emotional response in action. It’s not just about dogs and bells; it’s about us humans too, and our complex emotional landscapes.We can be conditioned to feel fear, pleasure, anxiety, excitement, and a whole spectrum of other emotions in response to things that were initially neutral.

This can happen through classical conditioning, where a neutral stimulus gets paired with an unconditioned stimulus that naturally elicits an emotional response. Over time, the neutral stimulus alone can trigger that same emotion.

“The heart has its reasons which reason knows nothing of.”

Blaise Pascal (paraphrased for emotional conditioning)

For example, if someone had a terrifying experience at a hospital as a child (unconditioned stimulus, fear), they might develop a conditioned fear response to the smell of antiseptic (neutral stimulus, now conditioned stimulus). Even years later, that smell can trigger anxiety and dread. On the flip side, positive associations can also be formed. If a particular song was playing during a really happy event, hearing that song later can bring on feelings of joy and nostalgia.

Physiological and Behavioral Manifestations

It’s not all in your head; conditioned responses have some serious physical and behavioral game. When your brain gets conditioned, it’s not just sending out emotional signals. It’s also kicking off a cascade of bodily reactions and influencing what you actually do. These changes can be subtle or really obvious, and they’re a key part of how conditioning shapes our lives.These responses can show up in a ton of ways, impacting everything from our heart rate to our habits.

It’s like our bodies and actions are on autopilot, responding to cues that used to mean nothing but now carry a whole lot of weight.Here’s a look at some common ways conditioned responses manifest:

- Physiological Changes: These are the involuntary bodily reactions that get triggered. Think of it as your body’s built-in alert system or reward system going haywire in response to a conditioned stimulus.

- Heart Rate and Blood Pressure: A conditioned stimulus, like the sound of a police siren (if previously associated with a stressful event), can cause your heart to race and your blood pressure to spike.

Conversely, a stimulus paired with relaxation might lower these.

- Respiration: Breathing patterns can change. A fearful conditioned response might lead to shallow, rapid breaths, while a comforting conditioned stimulus could promote deeper, slower breathing.

- Gastrointestinal Responses: Nausea or digestive changes can be conditioned. For instance, if you felt sick after eating a certain food during an illness, you might feel nauseous just thinking about that food later.

- Pupil Dilation: Our pupils can dilate in response to stimuli that are associated with arousal or interest, even if the stimulus itself isn’t inherently exciting.

- Sweating: Increased perspiration can be a conditioned response to stimuli associated with anxiety or fear.

- Heart Rate and Blood Pressure: A conditioned stimulus, like the sound of a police siren (if previously associated with a stressful event), can cause your heart to race and your blood pressure to spike.

- Behavioral Changes: These are the actions or tendencies that develop as a result of conditioning. They’re the outward signs that a conditioned response is happening.

- Avoidance Behaviors: If a certain place or situation has been consistently paired with negative experiences (like fear or pain), individuals may develop an automatic tendency to avoid it. This is super common in phobias.

- Approach Behaviors: On the flip side, stimuli associated with pleasure or reward can lead to an automatic desire to approach them. Think of someone rushing to the kitchen when they hear the microwave beep if it signals food.

- Habits and Compulsions: Many everyday habits, and even some compulsive behaviors, have roots in conditioning. A specific cue might trigger a routine action that has been reinforced in the past.

- Performance Changes: In sports or other performance-based activities, certain cues can become conditioned to trigger optimal or suboptimal performance levels based on past experiences.

- Food Preferences and Aversions: As mentioned earlier, our likes and dislikes for certain foods can be heavily influenced by conditioning, especially if they were paired with illness or pleasure.

Real-World Applications and Examples

Conditioned responses are way more than just textbook theories; they’re happening all around us, shaping our daily lives in ways we might not even realize. From the gut feelings we get when we hear a certain song to how we react to brand logos, these learned associations are a fundamental part of human behavior. Understanding them is like getting a cheat code for navigating the world, especially when it comes to influencing behavior, treating mental health, and even getting people to buy stuff.Think about it: our brains are constantly making connections.

That little jolt of anxiety when you see a specific email notification? That’s a conditioned response. Or maybe the way you automatically reach for a coffee when you wake up, even before you’re fully conscious. These aren’t random; they’re the result of learning through association, a core concept in psychology that has some seriously cool real-world implications.

Everyday Scenario: The “Uh-Oh” Feeling

Imagine Sarah. Every morning, she used to get a notification from her boss on her work phone, usually followed by a demanding request or a problem to solve. Initially, the notification sound itself was just a neutral stimulus. But after weeks of this pattern, the sound of that specific notification started to trigger a feeling of dread and a knot in her stomach, even before she saw what the message was.

The notification sound, once neutral, became a conditioned stimulus, eliciting a conditioned emotional response of anxiety and apprehension, much like the original feeling of stress caused by the boss’s demands.

Practical Applications of Understanding Conditioned Responses

Knowing how conditioned responses work is like having a superpower in several key areas. It helps us understand why people behave the way they do and allows us to strategically influence those behaviors. Whether it’s helping someone overcome a phobia, getting you to click on an ad, or making learning more effective, the principles of conditioning are everywhere.Here’s a rundown of where this knowledge really shines:

- Therapy: This is huge! Therapies like systematic desensitization use conditioning to help people overcome phobias and anxiety disorders. By gradually exposing individuals to their fears in a controlled, relaxed environment, therapists can help unlearn the conditioned fear response.

- Marketing and Advertising: Ever wonder why your favorite celebrities endorse certain products, or why ads are so catchy and repetitive? Marketers use classical conditioning all the time. They pair products (neutral stimulus) with positive emotions, attractive imagery, or familiar music (unconditioned stimuli) to create a positive association (conditioned response) with the product itself. Think of that catchy jingle that gets stuck in your head – it’s designed to make you feel good about the brand.

- Education: Teachers can use conditioning to create positive learning environments. Associating the classroom with engaging activities, positive reinforcement, and a sense of safety can lead to students feeling more motivated and less anxious about learning.

- Behavior Modification: In parenting, training animals, or even in workplace motivation, understanding how to reinforce desired behaviors and extinguish undesired ones is key. This often involves creating positive associations with good habits and negative ones with bad.

- Health and Medicine: Even our bodies can exhibit conditioned responses. For instance, a person who has experienced nausea after chemotherapy might develop an aversion to certain foods they ate before treatment, even if those foods weren’t the cause. This is a conditioned taste aversion.

Ivan Pavlov’s Salivating Dogs: A Classic Experiment

One of the most iconic experiments demonstrating conditioned responses comes from the brilliant mind of Ivan Pavlov, a Russian physiologist who was initially studying digestion in dogs. He noticed that his canine subjects would start salivating not just when food was presented, but also when they saw the lab assistant who usually brought the food, or even when they heard the footsteps of that assistant.

This sparked a whole new line of inquiry.Pavlov decided to systematically investigate this phenomenon. He began by presenting dogs with a neutral stimulus, such as a bell. At first, the bell elicited no salivation – it was just a sound. Then, he paired the ringing of the bell with the presentation of food (an unconditioned stimulus). The food naturally caused the dogs to salivate (an unconditioned response).

After repeatedly pairing the bell with food, the dogs began to associate the bell with the impending arrival of food. Eventually, the sound of the bell alone was enough to make the dogs salivate, even in the absence of food. The bell had transformed from a neutral stimulus into a conditioned stimulus, triggering a conditioned response of salivation.

Conceptual Representation of a Conditioned Response

To really nail down the mechanics, let’s break down the Pavlovian experiment into its core components. It’s like dissecting a hit song to see what makes it catchy – you identify the key elements and how they interact.Here’s a table showing the transformation:

| Unconditioned Stimulus (UCS) | Unconditioned Response (UCR) | Neutral Stimulus (NS) | Conditioned Stimulus (CS) | Conditioned Response (CR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food | Salivation | Bell | Bell (after pairing with food) | Salivation (to the bell) |

In this setup, the food naturally and automatically triggers salivation. The bell, initially, means nothing to the dog in terms of food. But by consistently presenting the bell right before the food, the dog learns to anticipate the food when it hears the bell. The bell then becomes a signal, a conditioned stimulus, that can elicit the same response – salivation – as the food did originally.

It’s a powerful demonstration of how learning through association can fundamentally alter our responses to the world around us.

Factors Influencing Conditioned Responses: What Is A Conditioned Response In Psychology

Alright, so we’ve talked about what a conditioned response is, how it got started, and how it all works. But here’s the tea: not all conditioning is created equal. Just like some TikTok trends catch on faster than others, the way we learn these responses isn’t always a straight shot. A bunch of things can totally tweak how quickly and how strongly that conditioned response shows up.

Think of it like trying to master a new dance move – sometimes you nail it on the first try, and sometimes you’re flailing for days.So, what’s the secret sauce? It boils down to a few key ingredients that make or break the learning process. These aren’t just random factors; they’re the nuts and bolts that determine if that bell is going to make your dog drool or just be a noise.

Timing and Intensity of Stimuli

When it comes to getting a conditioned response locked in, timing is everything. Imagine you’re trying to get your squad to hype you up for a big game. You want that energyright* before you step onto the court, not an hour later. The same goes for conditioning. The sweet spot for pairing the neutral stimulus (like a bell) with the unconditioned stimulus (like food) is crucial.

If they happen too far apart, your brain doesn’t make the connection.

The closer in time the neutral stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus occur, the stronger and faster the conditioning will be. This is often referred to as the “temporal relationship.”

Intensity also plays a major role. A super loud bell or a really strong-smelling treat is going to grab your attention way more than a whisper or a faint scent. A more intense unconditioned stimulus can often lead to a stronger conditioned response, even if the timing isn’t absolutely perfect. Think about a really startling noise versus a gentle tap – one is way more likely to trigger an immediate reaction.

Contiguity and Contingency in Learning

These two terms are like the dynamic duo of conditioning. Contiguity is all about proximity – how close together in space and time the stimuli are. It’s that “blink and you’ll miss it” connection. If the bell rings right before the food appears, that’s high contiguity. If there’s a long gap, or they happen in different rooms, contiguity is low, and learning suffers.

Contingency, on the other hand, is about predictability. It’s the “if this, then that” relationship. Does the bell

- reliably* signal that food is coming? Or does it sometimes ring and nothing happens? When the neutral stimulus is consistently followed by the unconditioned stimulus, there’s a strong contingency, and conditioning is way more likely to happen. It’s like knowing your favorite streamer will

- always* drop a giveaway when they hit a certain subscriber count – you’re going to be watching closely.

Here’s a breakdown of how these work:

- High Contiguity & High Contingency: This is the jackpot! Fast and strong conditioning. Think Pavlov’s dogs – bell always rings, food always follows, and it happens super close together.

- High Contiguity & Low Contingency: The neutral stimulus happens right before the unconditioned stimulus, but not every time. This can lead to weaker conditioning or even extinction if the pattern is broken too often.

- Low Contiguity & High Contingency: The stimuli are predictable but separated by a significant time or space. Conditioning might still happen, but it’ll be slower and less robust.

- Low Contiguity & Low Contingency: This is a recipe for no conditioning at all. If things are far apart and unpredictable, your brain just doesn’t see a connection.

Individual Differences and Biological Predispositions

Now, let’s get personal. Not everyone is wired the same way, right? Just like some people are natural athletes and others are more into coding, our biological makeup and individual experiences can totally influence how we condition.Some folks might be genetically predisposed to be more sensitive to certain stimuli. Think about people who are naturally more anxious or have a lower threshold for fear.

They might develop conditioned fear responses more easily and intensely than someone who’s more laid-back. This is where nature meets nurture.Your past experiences also play a huge role. If you had a really negative experience with a certain type of food as a kid, you might develop a conditioned taste aversion to it very quickly, even if it was just a mild stomach ache.

Conversely, if someone has had positive associations with a particular sound, they might be more resistant to forming a negative conditioned response to it. It’s like how some people can handle spicy food like pros because they’ve built up a tolerance, while others are crying after one bite.It’s also worth noting that different species have different biological readiness for certain types of conditioning.

For instance, birds are easily conditioned to avoid foods that cause nausea (taste aversion), which is a survival mechanism. Humans, while capable of a wide range of conditioning, also have complex cognitive processes that can influence the learning.

Imagine a dog drooling at the sound of a bell – that’s a conditioned response! We learn these fascinating connections all the time, exploring how do we learn psychology. Understanding these learned associations helps us grasp why a conditioned response, like that drooling dog, becomes automatic after pairing stimuli.

Distinguishing from Other Learning Concepts

Alright, so we’ve been diving deep into the world of conditioned responses, but to really get it, we gotta know what it

isn’t*. Think of it like this

you can’t just call any old reaction a conditioned response. It’s gotta fit the bill, and that means understanding how it stacks up against other ways we learn and react. We’re talking about the OG reactions and the ones we pick up through different kinds of training.This section is all about sharpening our focus. We’ll break down the nitty-gritty differences between a conditioned response and its unconditioned cousin, and then we’ll throw in operant conditioning for a real showdown.

By the end, you’ll be a pro at spotting what makes a conditioned response totally unique.

Conditioned Response Versus Unconditioned Response

Let’s get this straight: an unconditioned response is like your body’s built-in reflexes, the stuff that happens without you even trying. It’s wired in, no learning required. A conditioned response, on the other hand, is something you learn to do. It’s a learned reaction that gets triggered by something that

used* to be neutral.

Here’s the lowdown:

- Unconditioned Response (UCR): This is the natural, unlearned reaction to a stimulus. Think of it as your body’s automatic “uh-oh” or “yum!” reflex.

- Unconditioned Stimulus (UCS): This is the thing that naturally makes you have that unconditioned response. It’s the trigger for the automatic reaction.

- Conditioned Response (CR): This is the learned reaction to a previously neutral stimulus. It’s similar to the UCR, but it’s triggered by something that

-became* meaningful through association. - Conditioned Stimulus (CS): This is the stimulus that was originally neutral but, after being paired with the UCS, now elicits the CR.

Basically, the UCR is the original, unlearned reaction. The CR is thelearned* version of that same reaction, triggered by a new signal. It’s like your body’s version of “if this, then that,” but the “this” part got changed up through experience.

Conditioned Response Versus Operant Conditioning

Now, let’s talk about operant conditioning. This is where things get really interesting because it’s all about consequences. While classical conditioning (which gives us conditioned responses) is about associating stimuli, operant conditioning is about associating

behaviors* with their outcomes.

Think of it like this:

- Classical Conditioning (Conditioned Response): Focuses on involuntary, automatic responses. It’s about what happens

-before* the response, linking stimuli. Pavlov’s dogs salivating at the sound of a bell is the classic example. The bell (CS) becomes associated with food (UCS), leading to salivation (CR). - Operant Conditioning: Focuses on voluntary behaviors. It’s about what happens

-after* the behavior, linking the behavior to reinforcement or punishment. If you press a lever (behavior) and get a treat (reinforcement), you’re more likely to press the lever again. If you touch a hot stove (behavior) and get burned (punishment), you’ll be less likely to do it again.

The key difference is voluntary versus involuntary. Conditioned responses are typically involuntary, like a reflex. Operant conditioning deals with behaviors youchoose* to do, or at least have some control over, and then learn to repeat or avoid based on what happens next. It’s the difference between a sneeze (involuntary, classical) and deciding to study for a test because you want a good grade (voluntary, operant).

Unique Characteristics of Conditioned Responses

So, what makes a conditioned response stand out from the crowd of learning concepts? It’s all about how it’s formed and what it does. These aren’t just random reactions; they have a specific DNA.Here are the standout features:

- Involuntary Nature: Conditioned responses are typically automatic and outside of conscious control. You don’t decide to feel anxious when you hear a certain song; it just happens.

- Association-Based Learning: They are formed through the repeated pairing of a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus. It’s all about building connections between events.

- Stimulus Substitution (or Generalization): The conditioned stimulus comes to elicit a response similar to the unconditioned response. It’s like the new signal is “standing in” for the original one.

- Acquisition, Extinction, and Spontaneous Recovery: Conditioned responses follow predictable patterns of learning and forgetting. They can be acquired, fade away if the association is broken (extinction), and sometimes pop back up even after extinction (spontaneous recovery), showing how deeply ingrained they can become.

- Emotional and Physiological Impact: Conditioned responses often involve strong emotional or physiological reactions, like fear, excitement, or nausea, making them powerful drivers of behavior.

Think of phobias. Someone might develop a fear of spiders (conditioned response) after a traumatic encounter with one (unconditioned stimulus). The sight of any spider, even a tiny, harmless one (conditioned stimulus), can trigger intense fear (conditioned response). This reaction is involuntary, learned through association, and can be incredibly potent, demonstrating the unique power of conditioned responses in shaping our internal and external worlds.

Illustrative Scenarios and Demonstrations

Let’s dive into some real-world scenarios to really get a grip on how conditioned responses play out. Think of it like watching a movie where a character develops a totally unexpected reaction to something super ordinary, and then seeing how that reaction can fade away. It’s all about building connections and then, sometimes, unbuilding them.This section is all about painting a picture with words, showing you exactly what a conditioned response looks like in action and how it can be managed.

We’ll explore how these automatic reactions pop up and how, with a little effort, they can become a thing of the past.

Hypothetical Scenario: The Ringtone and the Jitters

Imagine a dude named Alex, who’s just landed his dream job. His company uses a super distinctive, almost annoying, ringtone for all incoming calls. For the first few weeks, Alex is on cloud nine, buzzing with excitement every time his phone rings because it means a new client, a new opportunity. He starts associating that specific, tinny sound with feelings of elation and success.

Fast forward a few months, and Alex is drowning in work. The phone rings non-stop, and the constant barrage of the same ringtone, once a harbinger of good things, now triggers a wave of anxiety and a subtle, involuntary tightening in his chest. He finds himself dreading the sound, even when he knows it’s just a routine call. The once positive association has flipped; the ringtone (neutral stimulus) has become a conditioned stimulus, reliably producing a feeling of unease and physical tension (conditioned response) that mirrors the stress he’s experiencing.

Demonstration of Extinction: The Phantom Buzz, What is a conditioned response in psychology

Let’s follow Alex’s journey as he starts to manage his anxiety. He realizes the ringtone is the culprit. His boss agrees to change the company’s notification sounds to something less jarring. For a while, Alex still feels a flicker of unease when he hears the old ringtone from a neighbor’s phone or a random commercial. However, as he’s exposed to the new, neutral notification sounds at work and the old ringtone becomes increasingly rare, the association starts to weaken.

He consciously reminds himself that the old ringtone no longer signifies overwhelming work demands. Over time, the anticipatory anxiety associated with the sound diminishes. Eventually, the old ringtone becomes just another sound in the background, no longer triggering that gut-level stress response. This gradual fading of the conditioned response, through repeated exposure to the conditioned stimulus without the presence of the original unconditioned stimulus (in this case, overwhelming work pressure), is known as extinction.

Conditioned Responses in Animals

Animals are total pros at developing conditioned responses, and understanding these examples can really illuminate the core principles. These pairings show how an animal learns to associate a new stimulus with something that naturally triggers a reaction. It’s like their brains are wired to make these connections, and once they do, it can significantly shape their behavior.Here are some classic examples of stimulus-response pairings in animal conditioning:

- Pavlov’s Dogs:

- Unconditioned Stimulus (UCS): Food

- Unconditioned Response (UCR): Salivation

- Neutral Stimulus (NS): Bell

- Conditioned Stimulus (CS): Bell (after pairing with food)

- Conditioned Response (CR): Salivation (to the bell alone)

This is the OG, the one that started it all. Dogs naturally salivate when presented with food. By repeatedly ringing a bell just before giving them food, Pavlov trained the dogs to salivate at the sound of the bell itself, even without the food present.

- Fear Conditioning in Rats:

- UCS: Electric Shock

- UCR: Freezing, Increased Heart Rate

- NS: A specific tone or light

- CS: The tone or light (after pairing with shock)

- CR: Freezing, Increased Heart Rate (to the tone or light alone)

Researchers can condition a fear response in rats. By presenting a tone followed by a mild electric shock, the rats learn to associate the tone with danger and will exhibit fear responses (like freezing) when they hear the tone, even if no shock is delivered.

- Learned Aversions in Birds:

- UCS: Nausea-inducing substance (e.g., a chemical that makes them sick)

- UCR: Vomiting, avoidance of the substance

- NS: A specific color or taste of food

- CS: The color or taste (after pairing with the nausea-inducing substance)

- CR: Avoidance of food with that color or taste

Birds that eat a food item with a particular color or taste that makes them ill will learn to avoid similar-looking or tasting food in the future, even if it’s perfectly safe. This is a crucial survival mechanism.

Outcome Summary

Understanding what is a conditioned response in psychology offers a profound insight into the intricate tapestry of human and animal behavior. It reveals how experiences, both big and small, weave connections that guide our actions and feelings. By recognizing these learned associations, we gain the potential to consciously influence our own responses and to better understand the world around us, fostering growth and positive change.

FAQ

What is the difference between an unconditioned stimulus and a conditioned stimulus?

An unconditioned stimulus naturally and automatically triggers a response without any prior learning, like food triggering salivation. A conditioned stimulus, however, is a previously neutral stimulus that, after being repeatedly paired with an unconditioned stimulus, comes to elicit a conditioned response, such as a bell ringing before food is presented.

Can conditioned responses be unlearned?

Yes, conditioned responses can be unlearned through a process called extinction. This occurs when the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus, weakening the association over time until the conditioned response no longer occurs.

Are conditioned responses always voluntary?

Conditioned responses are not always voluntary; in fact, many are involuntary. For instance, a conditioned emotional response like fear to a specific sound is an automatic, reflexive reaction, not a consciously chosen behavior.

How quickly can a conditioned response be formed?

The speed at which a conditioned response is formed can vary greatly. Factors like the intensity of the stimuli, the timing of their presentation (contiguity), and the consistency of their pairing (contingency) all play a significant role in how quickly the association is learned.

Can a conditioned response be applied to positive emotions?

Absolutely. Just as negative emotions can be conditioned, positive emotions like pleasure or happiness can also become associated with neutral stimuli. This is often utilized in marketing and therapy to create positive associations with products or experiences.