A hypothesis is psychology’s foundational element, serving as the bedrock upon which scientific inquiry is built. This exploration delves into the multifaceted nature of hypotheses within the psychological research landscape, illuminating their critical role from initial observation to the rigorous testing of empirical data. Understanding what constitutes a robust psychological hypothesis is paramount for anyone seeking to unravel the complexities of the human mind and behavior.

The subsequent discussion meticulously dissects the various types of hypotheses, the nuanced process of their formulation, and their indispensable application across diverse subfields of psychology. We will navigate the journey from abstract ideas to concrete, testable predictions, illustrating how these fundamental propositions guide experiments, shape data interpretation, and ultimately contribute to the ever-expanding body of psychological knowledge. The construction and testing of a hypothetical study will further demystify these concepts, offering practical insights into the scientific method in action.

Defining a Hypothesis in Psychology

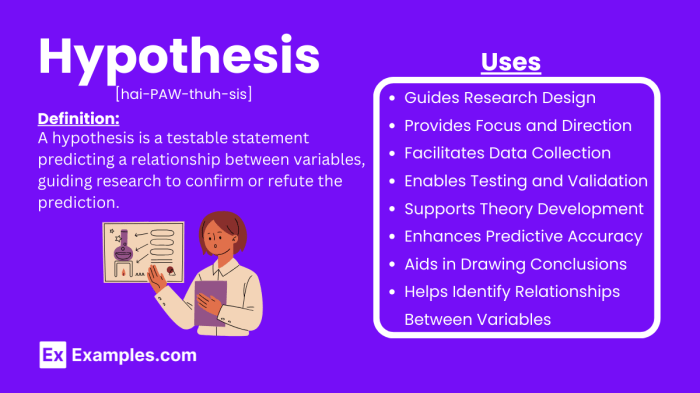

In the grand tapestry of psychological inquiry, the hypothesis stands as a crucial thread, weaving together observation and explanation. It is the bedrock upon which empirical investigations are built, guiding researchers towards uncovering the intricate workings of the human mind and behavior. Without a clearly articulated hypothesis, research can drift aimlessly, lacking focus and direction, much like a ship without a rudder on the vast ocean of knowledge.A hypothesis in psychology is essentially a specific, testable prediction about the relationship between two or more variables.

It is an educated guess, derived from existing theories, prior research, or even keen observation, that proposes a potential answer to a research question. This prediction is formulated in such a way that it can be empirically verified or refuted through systematic data collection and analysis.

The Fundamental Role of a Hypothesis in Psychological Research

The hypothesis serves as the compass and the blueprint for any psychological study. It defines the boundaries of the investigation, specifying what will be measured and how it will be examined. This focused approach ensures that the research is both efficient and meaningful, preventing the collection of irrelevant data and streamlining the analytical process. By providing a clear prediction, the hypothesis allows researchers to systematically test their ideas, contributing to the cumulative growth of psychological knowledge.

What Constitutes a Hypothesis in a Psychological Context

A psychological hypothesis is more than just a casual guess; it is a carefully crafted statement that meets specific criteria. It must be clear, concise, and unambiguous, leaving no room for misinterpretation. Furthermore, it must be falsifiable, meaning that it is possible to gather evidence that would prove it wrong. This falsifiability is the cornerstone of scientific inquiry, as it allows for the rigorous testing and refinement of ideas.Consider, for example, a hypothesis related to memory.

A well-formed hypothesis would not simply state “people forget things.” Instead, it would propose a specific relationship, such as: “Participants who study material using spaced repetition will recall significantly more information on a subsequent test compared to participants who use massed repetition.” This statement clearly identifies the variables (study method and recall performance) and predicts a specific outcome.

Essential Characteristics of a Well-Formed Psychological Hypothesis

For a hypothesis to be considered sound and scientifically useful, it must possess several key characteristics. These characteristics ensure that the hypothesis is not only testable but also contributes meaningfully to the field.

- Testability: The hypothesis must be amenable to empirical investigation. This means that the variables involved can be measured or manipulated, and the predicted relationship can be observed.

- Falsifiability: It must be possible to conceive of an outcome that would disprove the hypothesis. If a hypothesis cannot be disproven, it is not scientific.

- Clarity and Specificity: The hypothesis should be stated in precise language, avoiding vagueness. It should clearly define the variables and the expected direction of their relationship.

- Logical Basis: A good hypothesis is often grounded in existing psychological theories or previous research. It represents a logical extension or refinement of current knowledge.

- Predictive Power: The hypothesis should make a specific prediction about future observations. This predictive power is what allows for the testing and validation of the idea.

The Distinction Between a Hypothesis and a Theory in Psychology

While often used interchangeably in everyday language, a hypothesis and a theory are distinct concepts in psychology, differing in their scope and level of empirical support. A theory is a broad, well-substantiated explanation of some aspect of the natural world, based on a body of facts that have been repeatedly confirmed through observation and experiment. Theories are comprehensive frameworks that integrate and explain a wide range of phenomena.In contrast, a hypothesis is a specific, tentative statement that proposes a relationship between variables, often derived from a broader theory.

It is a focused prediction that can be tested through a single study or a series of studies. A hypothesis can be seen as a building block that, when tested and supported by evidence, can contribute to the development or refinement of a theory.

A theory is a grand structure of understanding, while a hypothesis is a single brick laid with care and tested for strength.

For instance, the theory of cognitive dissonance suggests that people experience discomfort when holding conflicting beliefs or attitudes and are motivated to reduce this discomfort. From this theory, one could derive a hypothesis such as: “Individuals who are induced to publicly advocate for a belief they privately disagree with will report a greater change in their private attitude towards that belief compared to those who are not induced to publicly advocate.” This hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction stemming from the broader theoretical framework of cognitive dissonance.

Types of Psychological Hypotheses

Just as a skilled farmer prepares the soil before planting seeds, psychologists meticulously craft hypotheses to guide their investigations. These hypotheses are not mere guesses, but rather educated predictions, carefully formulated to be tested and refined. Understanding the different forms these hypotheses can take is crucial for designing sound research and interpreting findings accurately, much like knowing the difference between a hardy grain and a delicate flower helps a farmer decide where and when to plant.In the realm of psychological inquiry, hypotheses serve as the bedrock of empirical investigation.

They provide a clear direction for research, allowing scientists to systematically explore relationships between variables and draw meaningful conclusions. The types of hypotheses employed often depend on the specific research question and the existing body of knowledge.

The Role and Structure of the Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis, often denoted as H₀, is a fundamental concept in statistical hypothesis testing. It represents a statement of no effect, no difference, or no relationship between variables. The primary purpose of the null hypothesis is to serve as a baseline against which the observed data is compared. Researchers aim to gather evidence that is sufficiently strong to reject this default assumption of no effect.

This approach, akin to a court of law presuming innocence until proven guilty, allows for a rigorous and objective evaluation of research findings.The structure of a null hypothesis is typically a declarative statement asserting the absence of a specific phenomenon. For instance, if a researcher is investigating the effect of a new therapy on anxiety levels, the null hypothesis would state that the therapy has no effect on anxiety.

A hypothesis in psychology serves as a foundational, testable prediction about behavior or mental processes. Understanding the academic pathway to generating and evaluating such hypotheses is crucial, and a comprehensive grasp of what is a bs in psychology provides this essential context. This academic foundation enables the rigorous formulation and empirical validation of psychological hypotheses.

H₀: There is no significant difference in anxiety levels between individuals who receive the new therapy and those who do not.

The Function and Structure of the Alternative Hypothesis

In direct contrast to the null hypothesis, the alternative hypothesis, denoted as H₁ or Hₐ, proposes that there is a significant effect, difference, or relationship between variables. It represents the researcher’s prediction or the theory being tested. The alternative hypothesis is what the researcher hopes to find evidence for. It can be formulated in a way that predicts the direction of the effect (directional hypothesis) or simply states that an effect exists without specifying its direction (non-directional hypothesis).The structure of an alternative hypothesis is a statement that contradicts the null hypothesis.

It specifies the expected outcome if the researcher’s theory or prediction is correct.

H₁: The new therapy significantly reduces anxiety levels.

Directional and Non-Directional Hypotheses

The distinction between directional and non-directional hypotheses lies in the specificity of the predicted outcome. A directional hypothesis makes a specific prediction about the direction of the relationship or difference, while a non-directional hypothesis simply predicts that a difference or relationship exists.A directional hypothesis is used when prior research or theoretical considerations strongly suggest the expected direction of the effect.

For example, a researcher might hypothesize that increased study time will lead to higher exam scores.

Directional Hypothesis Example: Students who engage in more than 10 hours of study per week will achieve significantly higher scores on the final examination compared to students who study less than 5 hours per week.

A non-directional hypothesis is employed when there is no clear expectation about the direction of the effect, or when the researcher wants to explore any potential difference or relationship. For instance, a researcher might investigate whether a new teaching method impacts student performance without specifying whether it will improve or decrease performance.

Non-Directional Hypothesis Example: There will be a significant difference in the academic performance of students taught using the new method compared to those taught using the traditional method.

Categorizing Psychological Hypotheses

Psychological hypotheses can be broadly categorized based on their complexity and the nature of the variables they relate. These categories help researchers structure their thinking and design appropriate methodologies for testing their predictions.Psychologists commonly utilize the following categories of hypotheses:

- Simple Hypotheses: These hypotheses propose a relationship between two variables. For example, a hypothesis stating that caffeine consumption increases alertness is a simple hypothesis as it links caffeine consumption (independent variable) to alertness (dependent variable).

- Complex Hypotheses: These hypotheses propose a relationship between more than two variables. They can involve multiple independent variables, multiple dependent variables, or a combination of both. An example would be a hypothesis suggesting that the interaction between sleep deprivation and stress levels influences cognitive performance.

- Associational Hypotheses: These hypotheses suggest that there is a relationship or correlation between two or more variables, but they do not imply causation. They state that as one variable changes, another variable tends to change in a specific direction. For instance, a hypothesis that there is a positive association between the number of social media interactions and feelings of loneliness would be an associational hypothesis.

- Causal Hypotheses: These hypotheses propose that one or more variables directly influence or cause changes in another variable. Establishing causality requires rigorous experimental designs, such as randomized controlled trials, to rule out alternative explanations. An example of a causal hypothesis would be: “Exposure to violent video games causes an increase in aggressive behavior among adolescents.”

Formulating a Testable Hypothesis

To move from a general observation to a scientific investigation, we must craft a hypothesis that can be rigorously tested. This process involves breaking down broad ideas into specific, measurable components, ensuring that our proposed explanation can be empirically validated or refuted. A well-formulated hypothesis acts as a compass, guiding the research design and data collection.The journey from a mere thought to a scientific inquiry hinges on the ability to transform an observation into a concrete, testable statement.

This requires a systematic approach, much like a Batak elder guiding the young ones through the intricate steps of weaving a traditional garment, ensuring each thread is placed with purpose and precision. We must learn to identify the core elements of our curiosity and translate them into a language that can be understood and verified by scientific methods.

Developing a Testable Hypothesis from an Observation, A hypothesis is psychology

The development of a testable hypothesis begins with careful observation of the world around us. These observations can arise from everyday experiences, previous research, or theoretical considerations. The key is to identify a phenomenon that sparks curiosity and can be investigated systematically.The following steps Artikel a procedure for transforming an initial observation into a robust, testable hypothesis:

- Identify a Specific Observation: Begin by pinpointing a particular event, behavior, or relationship that you find interesting or puzzling. For instance, observing that students who sit in the front row of a lecture hall seem to perform better on exams.

- Formulate a Preliminary Question: Based on the observation, develop a question that seeks to explain the phenomenon. In our example, this might be: “Why do students in the front row perform better on exams?”

- Review Existing Literature: Before proposing your own explanation, it is crucial to understand what is already known about the topic. This involves searching for relevant studies and theories that might shed light on your observation. You might discover research on attention, engagement, and seating position in educational settings.

- Propose a Tentative Explanation (Initial Hypothesis): Based on your observation and literature review, formulate a potential explanation for the phenomenon. This is an educated guess. For example, “Students who sit in the front row are more attentive during lectures.”

- Refine the Explanation into a Testable Hypothesis: This is the critical step where the tentative explanation is transformed into a clear, specific, and verifiable statement. It should predict a relationship between variables. The initial hypothesis might be refined to: “Students who choose to sit in the front row of a psychology lecture will achieve significantly higher scores on the subsequent exam compared to students who choose to sit in the back rows.”

- Identify Variables: Clearly define the key factors that are being investigated and how they will be measured. In our example, the independent variable is seating position (front vs. back row), and the dependent variable is exam score.

- Consider Potential Confounding Variables: Think about other factors that might influence the outcome and how they could be controlled or accounted for in the research design. For instance, prior academic performance, study habits, or motivation could also affect exam scores.

The Role of Hypotheses in Different Psychological Fields: A Hypothesis Is Psychology

Brothers and sisters, just as the ancestors guided our decisions with their wisdom, so too do hypotheses guide our quest for understanding the human mind. They are the compass and the map for our explorations in the vast landscape of psychology, pointing us toward undiscovered truths and helping us navigate the complexities of human behavior. Without a clear hypothesis, our research would be like a ship without a rudder, adrift on an endless sea of possibilities.The power of a hypothesis lies in its ability to focus our efforts and provide a framework for investigation.

It allows us to move beyond mere observation to a structured inquiry, testing specific ideas about how and why people think, feel, and act the way they do. This structured approach is essential across all branches of psychology, from the intricate workings of the mind to the dynamics of social interaction and the journey of human development.

Hypotheses in Cognitive Psychology Research

In the realm of cognitive psychology, where we delve into the processes of thinking, memory, and perception, hypotheses serve as crucial blueprints for experimentation. They allow us to dissect complex mental functions into testable components, unraveling the intricate mechanisms that underpin our understanding of the world. By formulating specific predictions, researchers can design studies to isolate variables and observe their effects on cognitive performance.Consider the process of memory.

A cognitive psychologist might hypothesize that the method of encoding information significantly impacts recall. For instance, a researcher could propose:

- Hypothesis: Participants who engage in elaborative rehearsal (e.g., connecting new information to existing knowledge) will demonstrate significantly better long-term recall of a word list compared to participants who engage in maintenance rehearsal (e.g., simple repetition).

This hypothesis allows for a direct comparison between two distinct memory strategies, enabling the researcher to collect data and draw conclusions about their relative effectiveness. Similarly, hypotheses are formulated to explore attention, problem-solving, language acquisition, and decision-making, each guided by a specific, testable prediction about underlying cognitive processes.

Hypotheses in Social Psychology Experiments

Social psychology, the study of how our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by the actual, imagined, or implied presence of others, relies heavily on hypotheses to understand interpersonal dynamics. Experiments in this field often aim to uncover the causes and consequences of social phenomena, and hypotheses provide the directional force for these investigations. They allow researchers to predict how individuals will behave in social situations based on specific manipulations of social variables.For example, when investigating conformity, a social psychologist might formulate a hypothesis such as:

- Hypothesis: Individuals are more likely to conform to the opinions of a unanimous majority, even when those opinions are clearly incorrect, than to the opinions of a dissenting minority.

This prediction can then be tested through classic experimental designs, like variations of the Asch conformity experiments, where participants are placed in situations where they must decide whether to agree with a group of confederates. Another common area for hypotheses is prejudice and discrimination. A researcher might hypothesize:

- Hypothesis: Exposure to positive intergroup contact, characterized by equal status and common goals, will reduce explicit and implicit prejudice towards members of an outgroup.

These hypotheses are not mere guesses but informed predictions based on existing theories and prior observations, guiding the design of experiments that can either support or refute these proposed relationships.

Examples of Hypotheses Used in Developmental Psychology Studies

Developmental psychology tracks the changes that occur throughout the human lifespan, from infancy to old age. Hypotheses in this field are crucial for understanding the predictable patterns of growth and the factors that influence these transformations. They allow researchers to investigate how cognitive abilities, social skills, emotional regulation, and physical development unfold over time.Here are some examples of hypotheses commonly found in developmental psychology research:

- Hypothesis (Infancy): Infants exposed to a variety of sensory stimuli (e.g., different textures, sounds, visual patterns) during the first year of life will exhibit more advanced object recognition skills at 18 months of age compared to infants with limited sensory exposure.

- Hypothesis (Childhood): Children who participate in structured peer play activities that involve negotiation and cooperation will demonstrate higher levels of prosocial behavior (e.g., sharing, helping) in later childhood compared to children who primarily engage in solitary play.

- Hypothesis (Adolescence): Adolescents who receive consistent and authoritative parenting, characterized by clear expectations and warm responsiveness, will report lower levels of risk-taking behavior and higher levels of self-esteem than adolescents with permissive or authoritarian parenting styles.

- Hypothesis (Adulthood): Older adults who actively engage in mentally stimulating activities, such as learning new skills or playing strategy games, will show slower rates of cognitive decline in areas like executive function and memory compared to their less engaged peers.

These hypotheses help developmental psychologists pinpoint specific age-related changes and identify environmental or experiential factors that may promote or hinder healthy development.

The Significance of Hypotheses in Clinical Psychology and Therapeutic Interventions

In clinical psychology, hypotheses are not just tools for research but are fundamental to diagnosing, understanding, and treating mental health conditions. They guide the formulation of treatment plans and the evaluation of their effectiveness. Clinicians often develop working hypotheses about the underlying causes of a patient’s distress, which then inform their therapeutic approach.A clinician might hypothesize that a client’s anxiety stems from specific maladaptive thought patterns.

This leads to a hypothesis like:

- Hypothesis: Cognitive restructuring techniques, aimed at identifying and challenging irrational beliefs, will lead to a significant reduction in reported anxiety symptoms and an increase in adaptive coping mechanisms in individuals diagnosed with Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

This hypothesis drives the selection of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques. The progress of the client is then monitored, and the initial hypothesis is continually refined or modified based on the observed outcomes. Furthermore, when developing new therapeutic interventions, researchers formulate hypotheses about how these interventions will work. For instance:

- Hypothesis: A mindfulness-based stress reduction program will lead to a statistically significant decrease in depressive symptom severity and an improvement in overall quality of life for individuals with recurrent major depressive disorder.

The effectiveness of a new medication or therapy is rigorously tested against such hypotheses, ensuring that interventions are evidence-based and truly beneficial for those seeking help. The empirical testing of these hypotheses allows for the continuous improvement and refinement of therapeutic practices, ultimately leading to better outcomes for individuals struggling with mental health challenges.

Constructing a Hypothesis for a Hypothetical Study

Now, let us venture into the practical realm of crafting a hypothesis. It is akin to a wise ancestor sketching a plan for a new village, outlining the expected harmony between the villagers and their surroundings. We shall build a scenario, then meticulously design a hypothesis, identify its core components, and finally, explore how we might test its validity, much like observing the growth of newly planted crops.Consider a scenario where a group of village elders notices that the younger generation, after spending more time engaged with modern electronic devices, seems to exhibit shorter attention spans during communal storytelling sessions.

This observation, though anecdotal, sparks a question about the relationship between screen time and focus. To understand this phenomenon scientifically, a psychologist might propose a study.

Designing a Specific, Testable Hypothesis

Based on the elders’ observations, a clear and measurable hypothesis can be formulated. This hypothesis will guide the entire research endeavor, ensuring that the investigation remains focused and that the findings can be definitively interpreted.

A hypothesis is a precise, testable prediction about the relationship between two or more variables.

For our hypothetical study, the hypothesis would be:

Increased daily exposure to digital screen time among adolescents will be associated with a significant decrease in sustained attention during non-digital cognitive tasks.

Identifying Independent and Dependent Variables

Every testable hypothesis contains specific elements that can be manipulated or measured. These are known as variables, and understanding them is crucial for designing a robust study. In our case, we have identified two key variables that we believe are related.The independent variable is the factor that the researcher manipulates or observes to see if it has an effect. It is the presumed “cause” in the hypothesized relationship.The dependent variable is the factor that is measured to see if it is affected by the independent variable.

It is the presumed “effect.”In our hypothesis:

- Independent Variable: Daily exposure to digital screen time (measured in hours per day).

- Dependent Variable: Sustained attention during non-digital cognitive tasks (measured by performance on tasks requiring prolonged focus, such as a sustained attention to response task or a complex puzzle).

Potential Methods for Testing This Hypothesis

To ascertain whether our hypothesis holds true, a structured approach to data collection and analysis is required. The chosen methods should be objective and allow for a clear assessment of the relationship between screen time and sustained attention. We will employ a descriptive approach to illustrate the procedure.Imagine a study involving a sample of 100 adolescents, aged 13-15, from various backgrounds within the community.

The research would proceed in the following manner:

- Participant Recruitment and Consent: Adolescents would be recruited, and their parents or guardians would provide informed consent for their participation. Ethical considerations, such as confidentiality and the right to withdraw, would be paramount.

- Screen Time Measurement: Participants would be asked to meticulously log their daily digital screen time for a period of two weeks. This would include time spent on smartphones, tablets, computers, and televisions for entertainment, social media, and gaming. To enhance accuracy, participants might also be encouraged to use screen time tracking applications on their devices.

This descriptive method allows for a detailed picture of individual usage patterns.

- Sustained Attention Assessment: Following the two-week logging period, each participant would undergo a series of standardized cognitive tasks designed to measure sustained attention. These tasks might include:

- Sustained Attention to Response Task (SART): In this task, participants are presented with a rapid sequence of stimuli (e.g., numbers) and are instructed to respond to each stimulus except for a specific “oddball” stimulus.

The ability to maintain focus and inhibit responses to the “oddball” is a measure of sustained attention.

- Complex Pattern Completion: Participants might be given a complex visual puzzle or a logical reasoning task that requires prolonged concentration to complete. The time taken to complete the task accurately, along with the number of errors made, would be recorded.

These tasks are chosen for their established ability to quantify attentional capabilities in a controlled, non-digital environment, providing a descriptive baseline of focus.

- Sustained Attention to Response Task (SART): In this task, participants are presented with a rapid sequence of stimuli (e.g., numbers) and are instructed to respond to each stimulus except for a specific “oddball” stimulus.

- Data Analysis: Once all data is collected, statistical analysis would be performed. A correlational analysis would be used to determine the strength and direction of the relationship between the average daily screen time and the scores on the sustained attention tasks. For instance, a negative correlation would suggest that as screen time increases, sustained attention decreases, supporting our hypothesis.

Descriptive statistics, such as means and standard deviations for both variables, would also be calculated to provide a comprehensive overview of the data.

Illustrating Hypothesis Testing Procedures

Hoo! Come now, let us delve into the heart of how we put our hunches, our hypotheses, to the test in the realm of psychology. It is not enough to simply have a clever idea; we must be able to examine it with the sharpest of tools, to see if the winds of evidence blow in its favor. This is where the rigorous dance of hypothesis testing begins, transforming abstract thoughts into observable truths, or sometimes, into new avenues of inquiry.Imagine, my friends, that we have a hypothesis that states: “Students who listen to classical music while studying will recall more information than those who study in silence.” This is our starting point, a clear prediction that we can set out to verify.

To do this, we would design an experiment, a controlled environment where we can observe the effects of our proposed cause.

Conceptual Experiment for Memory Recall

To test our hypothesis about classical music and memory, we would gather a group of participants, perhaps students from a local university. We would divide them into two groups, ensuring that these groups are as similar as possible in terms of their academic abilities, sleep patterns, and general study habits. This is crucial to ensure that any differences we observe are due to the music, and not some other factor.The first group, our experimental group, would be instructed to study a specific chapter of a textbook for a set amount of time while listening to classical music at a moderate volume.

The second group, our control group, would study the exact same chapter for the same duration, but in complete silence. After the study period, both groups would be given a standardized test designed to assess their recall of the material covered in the chapter. The scores from this test would then be compared.

Data Collection for Anxiety Levels Study

Now, let us consider a different scenario, where our hypothesis might be: “Exposure to nature documentaries reduces self-reported anxiety levels in adults.” To collect data for this, we would first recruit a sample of adults who report experiencing moderate levels of anxiety. We would administer a validated anxiety questionnaire, such as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, to establish a baseline measure of their anxiety.Following this, participants would be randomly assigned to one of two conditions.

One group would watch a series of nature documentaries for a predetermined period, say, 30 minutes each day for a week. The other group, our control, might watch neutral documentaries, such as historical or travel programs, for the same duration and frequency. At the end of the week, all participants would complete the anxiety questionnaire again. The collected data would consist of these pre- and post-intervention anxiety scores for each individual in both groups.

Statistical Interpretation of Results

Once we have gathered our data, the real work of interpretation begins, and this is where the magic of statistics comes into play. We use statistical tests to determine if the differences we observe between our groups are likely due to the intervention we applied, or if they could have occurred by chance. For our memory recall experiment, we might use an independent samples t-test to compare the average test scores of the classical music group and the silence group.

The null hypothesis (H₀) states that there is no significant difference between the groups, while the alternative hypothesis (H₁) suggests that there is a significant difference.

Our statistical analysis will yield a p-value. If this p-value is below a predetermined significance level (commonly set at 0.05), we reject the null hypothesis and conclude that our intervention had a statistically significant effect. For instance, if the p-value for the memory recall study is 0.03, we would conclude that listening to classical music indeed led to significantly better recall than studying in silence.

Conversely, if the p-value is greater than 0.05, we would fail to reject the null hypothesis, meaning the observed difference could be due to random chance.

Contribution of a Rejected Hypothesis

Do not despair, my friends, if our carefully crafted hypothesis is rejected by the data! This is not a failure, but a stepping stone. Even a rejected hypothesis can illuminate the path forward in our quest for understanding. Consider a hypothesis that predicted a specific therapeutic intervention would cure a particular phobia. If the study shows no significant improvement, it does not mean the research is wasted.Instead, this rejection can lead us to question our initial assumptions.

Perhaps the intervention was not potent enough, or it was applied for too short a duration. It might also suggest that the phobia is influenced by factors we did not account for, such as underlying personality traits or past trauma. This negative result can prompt researchers to explore alternative explanations, refine existing theories, or even develop entirely new hypotheses that are more aligned with the observed data.

For example, a rejected hypothesis about a single treatment might lead to research into combined therapies or personalized approaches, ultimately deepening our understanding of the complex nature of phobias.

Visualizing Hypothesis Concepts

To truly grasp the essence of a hypothesis in psychology, employing visual aids proves invaluable. These representations allow us to move beyond abstract definitions and see the tangible connections and logical progression that underpin scientific inquiry. They help clarify the relationship between the variables we are interested in and the structured path from initial curiosity to a verifiable claim.Visualizing hypotheses transforms complex psychological relationships into understandable forms.

Whether it’s depicting the interplay of abstract concepts or mapping the journey of a research idea, these methods enhance clarity and facilitate deeper comprehension. They serve as powerful tools for both the researcher and the audience, making the scientific process more accessible and impactful.

Abstract Psychological Constructs Relationship Visualization

When dealing with psychological research, we often investigate relationships between constructs that are not directly observable, such as anxiety, motivation, or self-esteem. Visualizing these relationships helps to illustrate the hypothesized connection between them, making the abstract more concrete. A common way to represent this is through a simple diagram that shows how one construct is expected to influence or be associated with another.Consider the relationship between perceived social support and academic performance.

We can visualize this by drawing two distinct shapes, perhaps circles or ovals, each labeled with the name of the construct. An arrow originating from “Perceived Social Support” and pointing towards “Academic Performance” would indicate a directional hypothesis, suggesting that higher levels of social support lead to better academic outcomes. Alternatively, a double-headed arrow could represent a correlational hypothesis, indicating that these two constructs are related but without specifying causality.

The thickness or color of the arrow could even symbolize the expected strength of the relationship.

Flowchart from Research Question to Testable Hypothesis

The journey from a broad area of interest to a specific, testable hypothesis is a structured process. A flowchart effectively maps this progression, detailing each critical step. This visual tool guides researchers in refining their initial curiosity into a precise and falsifiable statement.The flowchart typically begins with a broad research area, such as “student well-being.” This then narrows down to a more specific research question, for instance, “Does mindfulness meditation impact student stress levels?” From this question, potential variables are identified: “mindfulness meditation practice” (independent variable) and “student stress levels” (dependent variable).

The next crucial step is to formulate a preliminary hypothesis, which might be a directional statement like, “Students who engage in regular mindfulness meditation will report lower levels of stress.” Finally, this preliminary hypothesis is refined into a testable hypothesis by ensuring it is specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART), leading to a statement like, “Participants in a 12-week mindfulness meditation program will exhibit a statistically significant reduction in self-reported stress scores compared to a control group.”

Graph Illustrating Hypothesis Testing Findings

Presenting the results of hypothesis testing often involves graphical representations that clearly communicate the relationship between variables and the statistical significance of the findings. A common and effective graph for illustrating findings related to a tested hypothesis is a bar chart or a scatterplot, depending on the nature of the variables and the hypothesis.For a hypothesis predicting a difference between groups, such as comparing the effectiveness of two different teaching methods on student learning, a bar chart is highly suitable.

Imagine a hypothesis stating that “Method A will result in higher test scores than Method B.” A bar chart would display two bars, one representing the average test scores for students taught with Method A and another for Method B. The height of each bar would correspond to the mean score. Error bars, often representing standard deviation or standard error, would be included to show the variability within each group.

If the hypothesis is supported, the bar for Method A would be noticeably higher than the bar for Method B, and statistical significance would be indicated, often with an asterisk or a letter notation above the bars.For hypotheses exploring the relationship between two continuous variables, such as the correlation between hours of sleep and cognitive function, a scatterplot is more appropriate.

Each point on the scatterplot represents an individual participant, with their hours of sleep plotted on the x-axis and their cognitive function score on the y-axis. If the hypothesis posits a positive correlation (e.g., “More sleep leads to better cognitive function”), the points would generally trend upwards from left to right. A regression line can be added to visually represent the strength and direction of this relationship.

Statistical measures like the correlation coefficient (r) would accompany the graph, and if the hypothesis is supported, the r-value would be statistically significant.

Conclusion

In essence, the journey through the realm of psychological hypotheses reveals them not merely as educated guesses, but as sophisticated tools that drive scientific progress. From their initial conception rooted in observation to their critical role in experimental design and data interpretation, hypotheses are the engines of discovery in psychology. Whether null, alternative, directional, or non-directional, each type serves a distinct purpose in the meticulous process of understanding human behavior.

The ability to formulate, test, and critically evaluate hypotheses is therefore a cornerstone of psychological research, ensuring that our pursuit of knowledge remains both rigorous and insightful, even when initial predictions are ultimately disproven.

User Queries

What is the primary purpose of a hypothesis in psychology?

The primary purpose of a hypothesis in psychology is to provide a testable prediction or explanation for a phenomenon, guiding research and allowing for empirical investigation of specific relationships between variables.

How does a hypothesis differ from a research question?

A research question is a broad inquiry about a topic, whereas a hypothesis is a specific, testable statement that proposes an answer or relationship to that question.

Can a hypothesis be proven true?

In scientific methodology, hypotheses are not typically “proven” true. Instead, they are supported or refuted by evidence. If evidence consistently supports a hypothesis, it gains credibility, but absolute proof is generally avoided in favor of ongoing empirical validation.

What happens if a hypothesis is rejected?

A rejected hypothesis is still a valuable outcome. It helps to eliminate incorrect explanations, refine existing theories, and direct future research towards more promising avenues, thus contributing to the overall scientific understanding.

Are all psychological hypotheses quantitative?

While many psychological hypotheses are quantitative, aiming to measure and test relationships between numerical variables, qualitative hypotheses also exist, particularly in exploratory research, focusing on descriptive understanding and interpretation of phenomena.